Economy of Africa

Lagos is the largest city in Africa. | |

| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Population | 1.39 billion[1][2] |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth | 3.7% (2023 est.)[5] |

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

| 15.5% (2023 est.)[8] | |

Millionaires (US$) | 352,000 (2022)[9] |

| Public finances | |

| 62.4% of GDP (2023 est.)[10] | |

| Most numbers are from the International Monetary Fund. IMF Africa Datasets All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

| World economy |

|---|

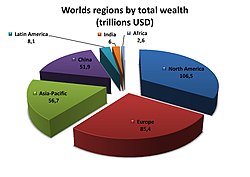

The economy of Africa consists of the trade, industry, agriculture, and human resources of the continent. As of 2019[update], approximately 1.3 billion people[11] were living in 53 countries in Africa. Africa is a resource-rich continent.[12][13] Recent growth has been due to growth in sales, commodities, services, and manufacturing.[14] West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa and Southern Africa in particular, are expected to reach a combined GDP of $29 trillion by 2050.[15]

In March 2013, Africa was identified as the world's poorest inhabited continent; however, the World Bank expects that most African countries will reach "middle income" status (defined as at least US$1,025 per person a year) by 2025 if current growth rates continue.[16] There are a number of reasons for Africa's poor economy: historically, even though Africa had a number of empires trading with many parts of the world, many people lived in rural societies; in addition, European colonization and the later Cold War created political, economic and social instability.[17]

However, as of 2013[update], Africa was the world's fastest-growing continent at 5.6% a year, and GDP is expected to rise by an average of over 6% a year between 2013 and 2023.[12][18] In 2017, the African Development Bank reported Africa to be the world's second-fastest growing economy, and estimates that average growth will rebound to 3.4% in 2017, while growth increased to 4.2% in 2018.[19] Growth has been present throughout the continent, with over one-third of African countries posting 6% or higher growth rates, and another 40% growing between 4% and 6% per year.[12] Several international business observers have also named Africa as the future economic growth engine of the world.[20]

List Of African countries by GDP

[edit]History

[edit]

For millennia, Africa's economy has been diverse, driven by extensive trade routes that developed between cities and kingdoms. Some trade routes were overland, some involved navigating rivers, still others developed around port cities. Large African empires became wealthy due to their trade networks, for example Ancient Egypt, Nubia, Mali, Ashanti, the Oyo Empire and Ancient Carthage . Some parts of Africa had close trade relationships with Arab kingdoms, and by the time of the Ottoman Empire, Africans had begun converting to Islam in large numbers. This development, along with the economic potential in finding a trade route to the Indian Ocean, brought the Portuguese to sub-Saharan Africa as an imperial force. Colonial interests created new industries to feed European appetites for goods such as palm oil, rubber, cotton, precious metals, spices, cash crops other goods, and integrated especially the coastal areas with the Atlantic economy.[21]

A significant factor on economic development was the gain of human capital by the elite. Between the 14th and 20th century, it can be observed that in regions with more elite violence and hence higher chances to die at a younger age the elite did not invest much in education. Therefore, their numeracy (as a measure of human capital) tends to be lower than in less safe countries and vice versa. This can explain the difference in economic development between the African regions.[22]•

20th century upheaval

[edit]Following the independence of African countries during the 20th century, economic, political and social upheaval consumed much of the continent. An economic rebound among some countries has been evident in recent years, however.[23]

The dawn of the African economic boom (which is in place since the 2000s) has been compared to the Chinese economic boom that had emerged in Asia since late 1970s.[24] In 2013, Africa was home to seven of the world's fastest-growing economies.[25]

As of 2018, Nigeria is the biggest economy in Africa by nominal GDP, followed by South Africa; in terms of PPP, Egypt is second biggest after Nigeria.[26] Equatorial Guinea has Africa's highest GDP per capita. Oil-rich countries such as Algeria, Libya and Gabon, and mineral-rich Botswana have emerged among the top economies since the 21st century, while Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo are potentially among the world's richest nations by natural resources, but have sunk into the list of the world's poorest nations due to pervasive political corruption, warfare, and emigration. Botswana stands out for its sustained strong and stable growth since independence.[27][28]

Current conditions

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (June 2024) |

The United Nations predicts Africa's economic growth will reach 3.5% in 2018 and 3.7% in 2019.[29] As of 2007, growth in Africa had surpassed that of East Asia. Data suggest parts of the continent are now experiencing fast growth, thanks to their resources and increasing political stability and 'has steadily increased levels of peacefulness since 2007'. The World Bank reports the economy of Sub-Saharan African countries grew at rates that match or surpass global rates.[30][31] According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the improvement in the region's aggregate growth is largely attributable to a recovery in Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa, three of Africa's largest economies.[29]

Sub-Saharan Africa was severely harmed when government revenue declined from 22% of GDP in 2011 to 17% in 2021. 15 African nations hold significant debt risk, and 7 are currently in financial crisis according to the IMF. The region went on to receive IMF Special Drawing Rights of $23 billion in 2021 to assist critical public spending.[32][33][34]

In 2007, the fastest-growing nations in Africa included Mauritania with growth at 19.8%, Angola at 17.6%, Sudan at 9.6%, Mozambique at 7.9% and Malawi at 7.8%. Other fast growers included Rwanda, Mozambique, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia. Growth was dismal, negative or sluggish in many parts of Africa including Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo and Burundi.[35]

As of a June 2010 report by McKinsey & Company, the rate of return on investment in Africa was the highest in the developing world.[36]

Debt relief is being addressed by some international institutions in the interests of supporting economic development in Africa. In 1996, the UN sponsored the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, subsequently taken up by the IMF, World Bank and the African Development Fund (AfDF) in the form of the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI).[37] As of 2013, the initiative has given partial debt relief to 30 African countries.[38]

In early 2021, the European Investment Bank, with the help of the Making Finance Work for Africa Partnership (MFW4A), surveyed 78 banks in Sub-Saharan Africa for the EIB Banking in Africa study. The banks that took part control nearly 30% of the continent's assets.[39][40] Almost two-thirds of Banks surveyed tightened lending rules, but more than 80% expanded their use of restructuring or loan moratoriums. Few banks were required to modify their employee levels, while slightly under one-third adjusted their prices. Approximately half of the answering banks had employee guarantees, the majority of which came from the central bank, the government, or an international financial institution.[39]

Fiscal stimulus packages in African countries through to mid-2020 amounted to roughly 1–2% of GDP, with monetary stimulus amounting to about 2% of GDP. This is close to the IMF's global average for low-income developing nations, which is around 2% of 2020 GDP over a one-year period from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, developing markets adopted a package worth around 4% of GDP, whereas advanced countries executed a package worth approximately 16% of GDP.[39][43][44] As African nations struggled to address the health and economic repercussions of the pandemic, the average fiscal deficit throughout Africa increased from 5% of GDP in 2019 to over 8% in 2020. Due to a lack of fiscal headroom, the deficit resulted in increasing borrowing, which African countries have less capacity to absorb than other developed economies.[39][45]

Northern and Southern African countries took the most total measures to address the COVID-19 recession, with an average of 14 measures per country.[46][47] 34 African nations adopted steps to increase liquidity and lower borrowing costs, mostly through lowering the policy rate. South Africa, for example, has decreased policy rates by 200 basis points or more.[46] The most used measure has been to modify the handling of nonperforming loans by lowering provisioning requirements. To help banks get through the COVID-19 recession, authorities limited dividends or other uses of earnings, permitted the temporary release of capital buffers, eased capital or liquidity requirements, or made other temporary adjustments to prudential standards.[46][48]

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, African private investment was steady in 2020, rising to $4.3 billion from $3.9 billion in 2019 as pipeline and current transactions were closed.[32] For resource-intensive nations, real per capita GDP is anticipated to stay below pre-pandemic levels until at least 2024, with growth of barely 1% per year in 2022 and 2023. Before the pandemic, 2% or more of growth had been anticipated.[49][50]

In 2023, East Africa had the largest crowding out pressures, whereas North Africa had the lowest.[51] In a recent report, female-led businesses were found more likely to invest in innovation, export goods and services, and provide employee training. Over half of the banks studied in this report indicated a lower percentage of non-performing loans among enterprises run by women than males.[52][53][54] Female-led firms also had lower rates of bankruptcy and were less likely to be affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.[55][56] 65% of banks in Africa were found to have a gender focused strategy in place.[52] The crowding out index showed improvement in 2024, but it remains at a high level.[57]

Africa’s share of global GDP has stagnated at 3.1% over the last two decades, with slow income convergence with developed nations.[58][59] Despite better market conditions in 2024, access to finance remains a significant barrier to development. In sub-Saharan Africa, private sector credit dropped from 56% of GDP in 2007 to 36% in 2022. This decline is linked to slow growth in private capital stock, which lags behind other regions, potentially hindering private sector growth and industrialization.[60]

A commonly cited barrier to development in Africa is the continent's relatively low level of industrialisation. Inadequate infrastructure, a lack of skilled labor, and limited access to finance, are hindering Africa's development.[61] In recent years, Africa has faced declines in foreign direct investment, overseas development aid, portfolio investments, and cross-border bank flows.[62][63][64]

To meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, Africa requires an additional $194 billion in annual financing.[65]

Trade growth

[edit]Trade has driven much of the growth in Africa's economy in the early 21st century. China and India are increasingly important trade partners; 12.5% of Africa's exports are to China, and 4% are to India, which accounts for 5% of China's imports and 8% of India's. The Group of Five (Indonesia, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates) are another increasingly important market for Africa's exports.[66]

Future

[edit]

Africa's economy—with expanding trade, English language skills (official in many Sub-Saharan countries), improving literacy and education, availability of splendid resources and cheaper labour force—is expected to continue to perform better into the future. Trade between Africa and China stood at US$166 billion in 2011.[67]

Africa will only experience a "demographic dividend" by 2035, when its young and growing labour force will have fewer children and retired people as dependents as a proportion of the population, making it more demographically comparable to the US and Europe.[68] It is becoming a more educated labour force, with nearly half expected to have some secondary-level education by 2020. A consumer class is also emerging in Africa and is expected to keep booming. Africa has around 90 million people with household incomes exceeding $5,000, meaning that they can direct more than half of their income towards discretionary spending rather than necessities. This number could reach a projected 128 million by 2020.[68]

During the President of the United States Barack Obama's visit to Africa in July 2013, he announced a US$7 billion plan to further develop infrastructure and work more intensively with African heads of state. A new program named Trade Africa, designed to boost trade within the continent as well as between Africa and the U.S., was also unveiled by Obama.[69]

With the introduction of the new economic growth and development plan introduced by the African Union members about 27 of its members who average some of the most developing economies of the continent will further boost economic social and political integration of the continent. The African Continental Free Trade Area will boost business activities between member states and within the continent. This will further reduce too much reliance on importation of finished products and raw materials in to the continent.[70]

The gap between rich and poor countries is predicted to continue to grow over the coming decades.[71]

Entrepreneurship

[edit]Entrepreneurship is key to growth. Governments will need to ensure business friendly regulatory environments in order to help foster innovation. In 2019, venture capital startup funding grew to 1.3 billion dollars, increasing rapidly. The causes are as of yet unclear, but education is certainly a factor.[72]

Climate change

[edit]Africa is warming faster than the rest of the world on average. Large portions of the continent may become uninhabitable as a result and Africa's gross domestic product (GDP) may decline by 2% as a result of a 1 °C rise in average world temperature, and by 12% as a result of a 4 °C rise in temperature. Crop yields are anticipated to drastically decrease as a result of rising temperatures and it is anticipated that heavy rains would fall more frequently and intensely throughout Africa, increasing the risk of floods.[73][74][75][76]

Additionally, Africa loses between $7 billion and $15 billion a year due to climate change, projected to reach up to $50 billion by 2030.[77]Causes of the economic underdevelopment over the years

[edit]The seemingly intractable nature of Africa's poverty has led to debate concerning its root causes. Endemic warfare and unrest, widespread corruption, and despotic regimes are both causes and effects of the continued economic problems. The decolonization of Africa was fraught with instability aggravated by cold war conflict. Since the mid-20th century, the Cold War and increased corruption, poor governance, disease and despotism have also contributed to Africa's poor economy.[78][79][80][81]

According to The Economist, the most important factors are government corruption, political instability, socialist economics, and protectionist trade policy.[72]

Infrastructure

[edit]

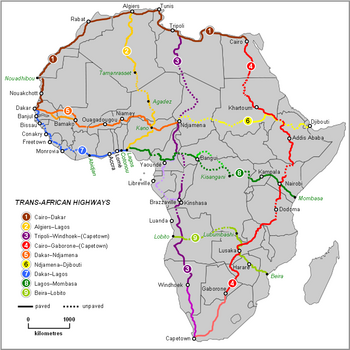

According to the researchers at the Overseas Development Institute, the lack of infrastructure in many developing countries represents one of the most significant limitations to economic growth and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).[82] Infrastructure investments and maintenance can be very expensive, especially in such areas as landlocked, rural and sparsely populated countries in Africa.[82]

It has been argued that infrastructure investments contributed to more than half of Africa's improved growth performance between 1990 and 2005 and increased investment is necessary to maintain growth and tackle poverty.[82] The returns to investment in infrastructure are very significant, with on average 30–40% returns for telecommunications (ICT) investments, over 40% for electricity generation, and 80% for roads.[82]

In Africa, it is argued that to meet the MDGs by 2015, infrastructure investments would need to reach about 15% of GDP (around $93 billion a year).[82] Currently, the source of financing varies significantly across sectors.[82] Some sectors are dominated by state spending, others by overseas development aid (ODA) and yet others by private investors.[82] In sub-Saharan Africa, the state spends around $9.4 billion out of a total of $24.9 billion.[82]

In irrigation, SSA[clarification needed] states represent almost all spending; in transport and energy a majority of investment is state spending; in Information and communication technologies and water supply and sanitation, the private sector represents the majority of capital expenditure.[82] Overall, aid, the private sector and non-OECD financiers between them exceed state spending.[82] The private sector spending alone equals state capital expenditure, though the majority is focused on ICT infrastructure investments.[82] External financing increased from $7 billion (2002) to $27 billion (2009). China, in particular, has emerged as an important investor.[82]

Colonialism

[edit]

The principal aim of colonial rule in Africa by European colonial powers was to exploit natural wealth in the African continent at a low cost. Some writers, such as Walter Rodney in his book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, argue that these colonial policies are directly responsible for many of Africa's modern problems.[79][83] Critics of colonialism charge colonial rule with injuring African pride, self-worth and belief in themselves. Other post-colonial scholars, most notably Frantz Fanon continuing along this line, have argued that the true effects of colonialism are psychological and that domination by a foreign power creates a lasting sense of inferiority and subjugation that creates a barrier to growth and innovation. Such arguments posit that a new generation of Africans free of colonial thought and mindset is emerging and that this is driving economic transformation.[84]

Historians L. H. Gann and Peter Duignan have argued that Africa probably benefited from colonialism on balance. Although it had its faults, colonialism was probably "one of the most efficacious engines for cultural diffusion in world history".[85] These views, however, are controversial and are rejected by some who, on balance, see colonialism as bad. The economic historian David Kenneth Fieldhouse has taken a kind of middle position, arguing that the effects of colonialism were actually limited and their main weakness wasn't in deliberate underdevelopment but in what it failed to do.[86] Niall Ferguson agrees with his last point, arguing that colonialism's main weaknesses were sins of omission.[87] Analysis of the economies of African states finds that independent states such as Liberia and Ethiopia did not have better economic performance than their post-colonial counterparts. In particular the economic performance of former British colonies was better than both independent states and former French colonies.[88]

Africa's relative poverty predates colonialism. Jared Diamond argues in Guns, Germs, and Steel that Africa has always been poor due to a number of ecological factors affecting historical development. These factors include low population density, lack of domesticated livestock and plants and the north–south orientation of Africa's geography.[89] However Diamond's theories have been criticized by some including James Morris Blaut as a form of environmental determinism.[90] Historian John K. Thornton argues that sub-Saharan Africa was relatively wealthy and technologically advanced until at least the seventeenth century.[91] Some scholars who believe that Africa was generally poorer than the rest of the world throughout its history make exceptions for certain parts of Africa. Acemoglue and Robinson, for example, argue that most of Africa has always been relatively poor, but "Aksum, Ghana, Songhay, Mali, [and] Great Zimbabwe ... were probably as developed as their contemporaries anywhere in the world."[92] A number of people including Rodney and Joseph E. Inikori have argued that the poverty of Africa at the onset of the colonial period was principally due to the demographic loss associated with the slave trade as well as other related societal shifts.[93] Others such as J. D. Fage and David Eltis have rejected this view.[94]

Language diversity

[edit]

African countries suffer from communication difficulties caused by language diversity. Greenberg's diversity index is the chance that two randomly selected people would have different mother tongues. Out of the most diverse 25 countries according to this index, 18 (72%) are African.[95] This includes 12 countries for which Greenberg's diversity index exceeds 0.9, meaning that a pair of randomly selected people will have less than 10% chance of having the same mother tongue. However, the primary language of government, political debate, academic discourse, and administration is often the language of the former colonial powers; English, French, or Portuguese.

Trade-based theories

[edit]Dependency theory asserts that the wealth and prosperity of the superpowers and their allies in Europe, North America and East Asia is dependent upon the poverty of the rest of the world, including Africa. Economists who subscribe to this theory believe that poorer regions must break their trading ties with the developed world in order to prosper.[96]

Less radical theories suggest that economic protectionism in developed countries hampers Africa's growth. When developing countries have harvested agricultural produce at low cost, they generally do not export as much as would be expected. Abundant farm subsidies and high import tariffs in the developed world, most notably those set by Japan, the European Union's Common Agricultural Policy, and the United States Department of Agriculture, are thought to be the cause. Although these subsidies and tariffs have been gradually reduced, they remain high.

Local conditions also affect exports; state over-regulation in several African nations can prevent their own exports from becoming competitive. Research in Public Choice economics such as that of Jane Shaw suggest that protectionism operates in tandem with heavy State intervention combining to depress economic development. Farmers subject to import and export restrictions cater to localized markets, exposing them to higher market volatility and fewer opportunities. When subject to uncertain market conditions, farmers press for governmental intervention to suppress competition in their markets, resulting in competition being driven out of the market. As competition is driven out of the market, farmers innovate less and grow less food further undermining economic performance.[97][98]

Governance

[edit]Although Africa and Asia had similar levels of income in the 1960s, Asia has since outpaced Africa, with the exception of a few extremely poor and war-torn countries like Afghanistan and Yemen. One school of economists argues that Asia's superior economic development lies in local investment. Corruption in Africa consists primarily of extracting economic rent and moving the resulting financial capital overseas instead of investing at home; the stereotype of African dictators with Swiss bank accounts is often accurate. University of Massachusetts Amherst researchers estimate that from 1970 to 1996, capital flight from 30 sub-Saharan countries totalled $187bn, exceeding those nations' external debts.[99] Authors Leonce Ndikumana and James K. Boyce estimate that from 1970 to 2008, capital flight from 33 sub-Saharan countries totalled $700bn.[100]

Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko became notorious for corruption, nepotism, and the embezzlement of between US$4 billion and $15 billion during his reign.[101][102] Socialist governments influenced by Marxism, and the land reform they have enacted, have also contributed to economic stagnation in Africa. For example, the regime of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, particularly the land seizures from white farmers, led to the collapse of the country's agricultural economy, which had formerly been one of Africa's strongest;[103] Mugabe had been previously supported by the USSR and China during the Zimbabwe War of Liberation. Tanzania was left as one of the world's poorest and most aid-dependent nations, and has taken decades to recover.[104] Since the abolition of the socialist one-party state in 1992 and the transition to democracy, Tanzania has experienced rapid economic growth, with growth of 6.5% in 2017.[105]

Foreign aid

[edit]Food shipments in case of dire local shortage are generally uncontroversial; but as Amartya Sen has shown, most famines involve a local lack of income rather than of food. In such situations, food aid—as opposed to financial aid—has the effect of destroying local agriculture and serves mainly to benefit Western agribusiness which are vastly overproducing food as a result of agricultural subsidies.

Historically, food aid is more highly correlated with excess supply in Western countries than with the needs of developing countries. Foreign aid has been an integral part of African economic development since the 1980s.[14]

The aid model has been criticized for supplanting trade initiatives.[14] Growing evidence shows that foreign aid has made the continent poorer.[106] One of the biggest critics of the aid development model is economist Dambisa Moyo (a Zambian economist based in the US), who introduced the Dead Aid model, which highlights how foreign aid has been a deterrent for local development.[107]

Today, Africa faces the problem of attracting foreign aid in areas where there is potential for high income from demand. It is in need of more economic policies and active participation in the world economy. As globalization has heightened the competition for foreign aid among developing countries, Africa has been trying to improve its struggle to receive foreign aid by taking more responsibility at the regional and international level. In addition, Africa has created the ‘Africa Action Plan’ in order to obtain new relationships with development partners to share responsibilities regarding discovering ways to receive aid from foreign investors.[108]

Trade blocs and multilateral organizations

[edit]The African Union is the largest international economic grouping on the continent. The confederation's goals include the creation of a free trade area, a customs union, a single market, a central bank, and a common currency (see African Monetary Union), thereby establishing economic and monetary union. The current plan is to establish an African Economic Community with a single currency by 2023.[109] The African Investment Bank is meant to stimulate development. The AU plans also include a transitional African Monetary Fund leading to an African Central Bank. Some parties support development of an even more unified United States of Africa.

International monetary and banking unions include:

Major economic unions are shown in the chart below.

| African Economic Community | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillar regional blocs (REC) |

Area (km²) |

Population | GDP (PPP) ($US) | Member states | |

| (millions) | (per capita) | ||||

| EAC | 5,449,717 | 343,328,958 | 737,420 | 2,149 | 8 |

| ECOWAS/CEDEAO | 5,112,903 | 349,154,000 | 1,322,452 | 3,788 | 15 |

| IGAD | 5,233,604 | 294,197,387 | 225,049 | 1,197 | 7 |

| AMU/UMA a | 6,046,441 | 106,919,526 | 1,299,173 | 12,628 | 5 |

| ECCAS/CEEAC | 6,667,421 | 218,261,591 | 175,928 | 1,451 | 11 |

| SADC | 9,882,959 | 394,845,175 | 737,392 | 3,152 | 15 |

| COMESA | 12,873,957 | 406,102,471 | 735,599 | 1,811 | 20 |

| CEN-SAD a | 14,680,111 | 29 | |||

| Total AEC | 29,910,442 | 853,520,010 | 2,053,706 | 2,406 | 54 |

| Other regional blocs |

Area (km²) |

Population | GDP (PPP) ($US) | Member states | |

| (millions) | (per capita) | ||||

| WAMZ 1 | 1,602,991 | 264,456,910 | 1,551,516 | 5,867 | 6 |

| SACU 1 | 2,693,418 | 51,055,878 | 541,433 | 10,605 | 5 |

| CEMAC 2 | 3,020,142 | 34,970,529 | 85,136 | 2,435 | 6 |

| UEMOA 1 | 3,505,375 | 80,865,222 | 101,640 | 1,257 | 8 |

| UMA 2 a | 5,782,140 | 84,185,073 | 491,276 | 5,836 | 5 |

| GAFTA 3 a | 5,876,960 | 1,662,596 | 6,355 | 3,822 | 5 |

| AES | 2,780,159 | 71,374,000 | 179,347 | 3 | |

During 2004. Sources: The World Factbook 2005, IMF WEO Database.

Smallest value among the blocs compared.

Largest value among the blocs compared.

1: Economic bloc inside a pillar REC.

2: Proposed for pillar REC, but objecting participation.

3: Non-African members of GAFTA are excluded from figures.

a: The area 446,550 km2 used for Morocco excludes all disputed territories, while 710,850 km2 would include the Moroccan-claimed and partially-controlled parts of Western Sahara (claimed as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic by the Polisario Front). Morocco also claims Ceuta and Melilla, making up about 22.8 km2 (8.8 sq mi) more claimed territory.

| |||||

Regional economic organizations

[edit]During the 1960s, Ghanaian politician Kwame Nkrumah promoted economic and political union of African countries, with the goal of independence.[110] Since then, objectives, and organizations, have multiplied. Recent decades have brought efforts at various degrees of regional economic integration. Trade between African states accounts for only 11% of Africa's total commerce as of 2012, around five times less than in Asia.[111] Most of this intra-Africa trade originates from South Africa and most of the trade exports coming out of South Africa goes to abutting countries in Southern Africa.[112]

There are currently eight regional organizations that assist with economic development in Africa:[113]

| Name of organization | Date created | Member countries | Cumulative GDP (in millions of US dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Community of West African States | 28 May 1975 | Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo | 657 |

| East African Community | 30 November 1999 | Burundi, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania | 232 |

| Economic Community of Central African States | 18 October 1983 | Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Guinea, São Tomé and Príncipe, Chad | 289 |

| Southern African Development Community | 17 August 1992 | Angola, Botswana, Eswatini (Swaziland), Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe | 909 |

| Intergovernmental Authority on Development | 25 November 1996 | Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan | 326 |

| Community of Sahel-Saharan States | 4 February 1998 | Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia, Libya, Mali, Morocco, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, São Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Chad, Togo, Tunisia | 1, 692 |

| Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa | 5 November 1993 | Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Eswatini (Swaziland), Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sudan, Zambia, Zimbabwe | 1,011 |

| Arab Maghreb Union | 17 February 1989 | Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Mauritania, Tunisia | 579 |

Economic variants and indicators

[edit]After an initial rebound from the 2009 world economic crisis, Africa's economy was undermined in the year 2011 by the Arab uprisings. The continent's growth fell back from 5% in 2010 to 3.4% in 2011. With the recovery of North African economies and sustained improvement in other regions, growth across the continent is expected to accelerate to 4.5% in 2012 and 4.8% in 2013.[citation needed] Short-term problems for the world economy remain as Europe confronts its debt crisis. Commodity prices—crucial for Africa—have declined from their peak due to weaker demand and increased supply, and some could fall further. But prices are expected to remain at levels favourable for African exporter.[114]

Regions

[edit]Economic activity has rebounded across Africa. However, the pace of recovery was uneven among groups of countries and subregions. Oil-exporting countries generally expanded more strongly than oil-importing countries. West Africa and East Africa were the two best-performing subregions in 2010.[115]

Intra-African trade has been slowed by protectionist policies among countries and regions, and remains low at 17 percent, compared to Europe, where intra-regional trade is at 69 percent.[116] Despite this, trade between countries belonging to the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), a particularly strong economic region, grew six-fold over the past decade up to 2012.[117] Ghana and Kenya, for example, have developed markets within the region for construction materials, machinery, and finished products, quite different from the mining and agriculture products that make up the bulk of their international exports.[118]

The African Ministers of Trade agreed in 2010 to create a Pan-Africa Free Trade Zone. This would reduce countries' tariffs on imports and increase intra-African trade, and it is hoped, the diversification of the economy overall.[119]

African nations

[edit]| Country | Total GDP (nominal) in 2019 (billion US$)[122] |

GDP per capita in 2019 (US$, PPP)[122] |

Average annual real GDP growth 2010–2019 (%)[122] |

HDI 2019[123] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 169.3 | 11,729 | 2.6 | 0.748 | |

| 89.4 | 7,384 | 1.9 | 0.581 | |

| 14.4 | 3,423 | 5.1 | 0.545 | |

| 18.5 | 17,949 | 4.3 | 0.735 | |

| 15.7 | 2,282 | 5.7 | 0.452 | |

| 3.1 | 821 | 2.0 | 0.433 | |

| 38.9 | 3,856 | 4.6 | 0.563 | |

| 2.0 | 7,471 | 2.9 | 0.665 | |

| 2.3 | 985 | −1.8 | 0.397 | |

| 10.9 | 1,654 | 2.2 | 0.398 | |

| 1.2 | 3,108 | 3.1 | 0.554 | |

| 49.8 | 1,015 | 6.1 | 0.480 | |

| 12.5 | 4,600 | −1.0 | 0.574 | |

| 3.3 | 5,195 | 6.6 | 0.524 | |

| 302.3 | 12,391 | 3.8 | 0.707 | |

| 11.8 | 19,291 | −2.9 | 0.592 | |

| 2.0 | 1,836 | 3.4 | 0.459 | |

| 4.6 | 9,245 | 2.4 | 0.611 | |

| 92.8 | 2,724 | 9.5 | 0.485 | |

| 16.9 | 16,273 | 3.7 | 0.703 | |

| 1.8 | 2,316 | 2.4 | 0.496 | |

| 67.0 | 5,688 | 6.5 | 0.611 | |

| 13.8 | 2,506 | 6.2 | 0.477 | |

| 1.4 | 2,429 | 3.8 | 0.480 | |

| 58.6 | 5,327 | 6.7 | 0.538 | |

| 95.4 | 4,985 | 5.6 | 0.601 | |

| 2.4 | 3,010 | 2.8 | 0.527 | |

| 3.2 | 1,601 | 2.7 | 0.480 | |

| 39.8 | 14,174 | −10.2 | 0.724 | |

| 14.1 | 1,720 | 3.4 | 0.528 | |

| 7.7 | 1,004 | 3.8 | 0.483 | |

| 17.3 | 2,508 | 4.3 | 0.434 | |

| 7.6 | 6,036 | 3.9 | 0.546 | |

| 14.0 | 23,819 | 3.6 | 0.804 | |

| 3.1 (2018)[124] | 11,815 (nominal, 2018)[124] | (N/A) | (N/A) | |

| 118.6 | 8,148 | 3.4 | 0.686 | |

| 15.2 | 1,302 | 5.4 | 0.456 | |

| 12.5 | 10,279 | 2.8 | 0.646 | |

| 12.9 | 1,276 | 5.9 | 0.394 | |

| 448.1 | 5,353 | 3.0 | 0.539 | |

| 22.0[125] | 25,639 (nominal)[125] | 2.1[126] | 0.850 (2003)[127] | |

| 10.1 | 2,363 | 7.6 | 0.543 | |

| 0.4 | 4,141 | 3.9 | 0.625 | |

| 23.6 | 3,536 | 5.3 | 0.512 | |

| 1.7 | 30,430 | 4.6 | 0.796 | |

| 4.2 | 1,778 | 4.4 | 0.452 | |

| 18.2 | 888.00 | (N/A) | 0.364 (2008)[128] | |

| 351.4 | 12,962 | 1.5 | 0.709 | |

| 4.9 | 862 | (N/A) | 0.433 | |

| 33.4 | 4,140 | −1.6 | 0.510 | |

| 60.8 | 2,841 | 6.7 | 0.529 | |

| 5.5 | 1,657 | 5.6 | 0.515 | |

| 38.8 | 11,125 | 1.8 | 0.740 | |

| 36.5 | 2,646 | 5.2 | 0.544 | |

| 24.2 | 3,526 | 4.3 | 0.584 | |

| 18.7 | 2,896 | 4.2 | 0.571 |

Economic sectors and industries

[edit]Because Africa's export portfolio remains predominantly based on raw material, its export earnings are contingent on commodity price fluctuations. This exacerbates the continent's susceptibility to external shocks and bolsters the need for export diversification. Trade in services, mainly travel and tourism, continued to rise in year 2012, underscoring the continent's strong potential in this sphere.[114][129][130]

Agriculture

[edit]

48% of working people in Africa work in agriculture, the highest in the world.[131] The situation whereby African nations export crops to the West while millions on the continent starve has been blamed on the economic policies of the developed countries. These advanced nations protect their own agricultural sectors with high import tariffs and offer government subsidies to their farmers.[132] which many contend leads the overproduction of such commodities as grain, cotton and milk. The impact of agricultural subsidies in developed countries upon developing-country farmers and international development is well documented. Agricultural subsidies can help drive prices down to benefit consumers, but also mean that unsubsidised developing-country farmers have a more difficult time competing in the world market;[133] and the effects on poverty are particularly negative when subsidies are provided for crops that are also grown in developing countries since developing-country farmers must then compete directly with subsidised developed-country farmers, for example in cotton and sugar.[134][135] The IFPRI has estimated in 2003 that the impact of subsidies costs developing countries $24 billion in lost incomes going to agricultural and agro-industrial production; and more than $40Bn is displaced from net agricultural exports.[136] The result of this is that the global price of such products is continually reduced until Africans are unable to compete, except for cash crops that do not grow easily in a northern climate.[129][130][137]

In recent years countries such as Brazil, which has experienced progress in agricultural production, have agreed to share technology with Africa to increase agricultural production in the continent to make it a more viable trade partner.[138] Increased investment in African agricultural technology in general has the potential to reduce poverty in Africa.[129][130][139] The demand market for African cocoa has experienced a price boom in 2008.[140] The Nigerian,[141] South African[142] and Ugandan governments have targeted policies to take advantage of the increased demand for certain agricultural products[143] and plan to stimulate agricultural sectors.[144] The African Union has plans to heavily invest in African agriculture[145] and the situation is closely monitored by the UN.[146]

Ticks are a constant pressure on the continent's livestock.[147] Although acaricides have been commonly used by farmers here, they are becoming less effective.[147] Tick vaccines are under development and may fill this void.[147]

Energy

[edit]

Africa has significant resources for generating energy in several forms (hydroelectric, reserves of petroleum and gas, coal production, uranium production, renewable energy such as solar, wind and geothermal). The lack of development and infrastructure means that little of this potential is actually in use today.[129][130] The largest consumers of electric power in Africa are South Africa, Libya, Namibia, Egypt, Tunisia, and Zimbabwe, which each consume between 1000 and 5000 KWh/m2 per person, in contrast with African states such as Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Tanzania, where electricity consumption per person is negligible.[148]

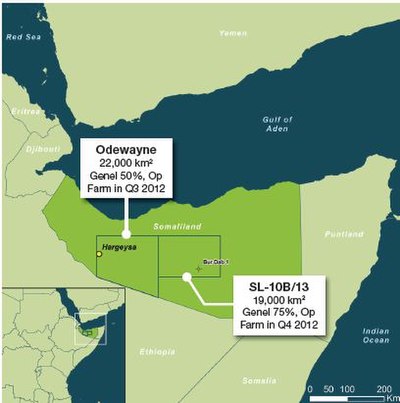

Petroleum and petroleum products are the main export of 14 African countries. Petroleum and petroleum products accounted for a 46.6% share of Africa's total exports in 2010; the second largest export of Africa as a whole is natural gas, in its gaseous state and as liquified natural gas, accounting for a 6.3% share of Africa's exports.[149] Only South Africa is using nuclear power commercially.[150]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Lack of infrastructure creates barriers for African businesses.[129][130] Although it has many ports, a lack of supporting transportation infrastructure adds 30–40% to costs, in contrast to Asian ports.[151]

Railway projects were important in mining districts from the late 19th century. Large railway and road projects characterize the late 19th century. Railroads were emphasized in the colonial era, and roads in 'post-colonial' times. Jedwab & Storeygard find that in 1960–2015 there were strong correlations between transportation investments and economic development. Influential political include pre-colonial centralization, ethnic fractionalization, European settlement, natural resource dependence, and democracy.[152]

Many large infrastructure projects are underway across Africa. By far, most of these projects are in the production and transportation of electric power. Many other projects include paved highways, railways, airports, and other construction.[151]

Telecommunications infrastructure is also a growth area in Africa. Although Internet penetration lags other continents, it has still reached 9%. As of 2011, it was estimated that 500,000,000 mobile phones of all types were in use in Africa, including 15,000,000 "smart phones".[153]

Mining and drilling

[edit]

The mineral industry of Africa is one of the largest mineral industries in the world. Africa is the second biggest continent, with 30 million km2 of land, which implies large quantities of resources.[129][130] For many African countries, mineral exploration and production constitute significant parts of their economies and remain keys to future economic growth. Africa is richly endowed with mineral reserves and ranks first or second in quantity of world reserves of bauxite, cobalt, industrial diamond, phosphate rock, platinum-group metals (PGM), vermiculite, and zirconium.

African mineral reserves rank first or second for bauxite, cobalt, diamonds, phosphate rocks, platinum-group metals (PGM), vermiculite, and zirconium. Many other minerals are also present in quantity. The 2005 share of world production from African soil is the following: bauxite 9%; aluminium 5%; chromite 44%; cobalt 57%; copper 5%; gold 21%; iron ore 4%; steel 2%; lead (Pb) 3%; manganese 39%; zinc 2%; cement 4%; natural diamond 46%; graphite 2%; phosphate rock 31%; coal 5%; mineral fuels (including coal) & petroleum 13%; uranium 16%.[citation needed]

Since Africa is home to large reserves of the minerals needed for the ongoing energy transition, i.e. the transition to renewable energy technologies, the predicted increase in global demand for these critical minerals could become a driver of sustainable economic development on the continent, not least for the mineral-rich countries of Africa.[154] The African Union has outlined a policy framework, the Africa Mining Vision, to leverage the continent’s mineral reserves in pursuit of sustainable development and socio-economic transformation.[155] A key ambition in this vision is to transform Africa's economies from today's high levels of commodity export to a larger share of industrial manufacturing of higher value-added products, an ambition that will require investments in capacity building, research and development.[154]

Manufacturing

[edit]

Both the African Union and the United Nations have outlined plans in modern years on how Africa can help itself industrialize and develop significant manufacturing sectors to levels proportional to the African economy in the 1960s with 21st-century technology.[156] This focus on growth and diversification of manufacturing and industrial production, as well as diversification of agricultural production, has fueled hopes that the 21st century will prove to be a century of economic and technological growth for Africa. This hope, coupled with the rise of new leaders in Africa in the future, inspired the term "the African Century", referring to the 21st century potentially being the century when Africa's vast untapped labor, capital, and resource potentials might become a world player. This hope in manufacturing and industry is helped by the boom in communications technology[157] and local mining industry[158] in much of sub-Saharan Africa. Namibia has attracted industrial investments in recent years[159] and South Africa has begun offering tax incentives to attract foreign direct investment projects in manufacturing.[160]

Countries such as Mauritius have plans for developing new "green technology" for manufacturing.[161] Developments such as this have huge potential to open new markets for African countries as the demand for alternative "green" and clean technology is predicted to soar in the future as global oil reserves dry up and fossil fuel-based technology becomes less economically viable.[162][163]

Nigeria in recent years has been embracing industrialization, It currently has an indigenous vehicle manufacturing company, Innoson Vehicle Manufacturing (IVM) which manufactures Rapid Transit Buses, Trucks and SUVs with an upcoming introduction of Cars.[164] Their various brands of vehicle are currently available in Nigeria, Ghana and other West African Nations.[165][166][167][168] Nigeria also has few Electronic manufacturers like Zinox, the first Branded Nigerian Computer and Electronic gadgets (like tablet PCs) manufacturers.[169] In 2013, Nigeria introduced a policy regarding import duty on vehicles to encourage local manufacturing companies in the country.[170][171] In this regard, some foreign vehicle manufacturing companies like Nissan have made known their plans to have manufacturing plants in Nigeria.[172] Apart from Electronics and vehicles, most consumer, pharmaceutical and cosmetic products, building materials, textiles, home tools, plastics and so on are also manufactured in the country and exported to other west African and African countries.[173][174][175] Nigeria is currently the largest manufacturer of cement in Sub-saharan Africa.[176] and Dangote Cement Factory, Obajana is the largest cement factory in sub-saharan Africa.[177] Ogun is considered to be Nigeria's industrial hub (as most factories are located in Ogun and even more companies are moving there), followed by Lagos.[178][179][180]

The manufacturing sector is small but growing in East Africa.[181] The main industries are textile and clothing, leather processing, agribusiness, chemical products, electronics and vehicles.[181] East African countries like Uganda also produce motorcycles for the domestic market.[182]

Investment and banking

[edit]

Africa's US$107 billion financial services industry will log impressive growth for the rest of the decade[which?] as more banks target the continent's emerging middle class.[183] The banking sector has been experiencing record growth, among others due to various technological innovations.[184]

China and India[185] have showed increasing interest in emerging African economies in the 21st century. Reciprocal investment between Africa and China increased dramatically in recent years[186][187] amidst the current world financial crisis.[188]

The increased investment in Africa by China has attracted the attention of the European Union and has provoked talks of competitive investment by the EU.[189] Members of the African diaspora abroad, especially in the EU and the United States, have increased efforts to use their businesses to invest in Africa and encourage African investment abroad in the European economy.[190]

Remittances from the African diaspora and rising interest in investment from the West will be especially helpful for Africa's least developed and most devastated economies, such as Burundi, Togo and Comoros.[191] However, experts lament the high fees involved in sending remittances to Africa due to a duopoly of Western Union and MoneyGram that is controlling Africa's remittance market, making Africa is the most expensive cash transfer market in the world.[192] According to some experts, the high processing fees involved in sending money to Africa are hampering African countries' development.[193]

Remittances continue to be the most important source of external financial flows to Africa, accounting for 3.8% of GDP in 2021. However, only approximately 30% of it is dedicated to economic activities, the majority of which are in the informal sector, limiting its potential for productive transformation.[52][194][195]

Angola has announced interests in investing in the EU, Portugal in particular.[196] South Africa has attracted increasing attention from the United States as a new frontier of investment in manufacture, financial markets and small business,[197] as has Liberia in recent years under their new leadership.[198]

There are two African currency unions: the West African Banque Centrale des États de l'Afrique de l'Ouest (BCEAO) and the Central African Banque des États de l'Afrique Centrale (BEAC). Both use the CFA franc as their legal tender. The idea of a single currency union across Africa has been floated, and plans exist to have it established by 2020, though many issues, such as bringing continental inflation rates below 5 percent, remain hurdles in its finalization.[199]

Stock exchanges

[edit]

As of 2012, Africa has 23 stock exchanges, twice as many as it had 20 years earlier. Nonetheless, African stock exchanges still account for less than 1% of the world's stock exchange activity.[200] The top ten stock exchanges in Africa by stock capital are (amounts are given in billions of United States dollars):[201] but nowadays there are around 29 stock exchanges in Africa:

- South Africa (82.88)(2014)[202]

- Egypt ($73.04 billion (30 November 2014 est.))[203]

- Morocco (5.18)

- Nigeria (5.11) (Actually has a market capitalisation value of $39.27 Bln)[204]

- Kenya (1.33)

- Tunisia (0.88)

- BRVM (regional stock exchange whose members include Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo: 6.6)

- Mauritius (0.55)

- Botswana (0.43)

- Ghana (.38)

| Stock Exchange Name | City | Country | Year Founded | Currency | Value in USD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola Debt and Stock Exchange | Luanda | 1995 | Angolan Kwanza | ||

| Botswana Stock Exchange | Gaborone | 1995 | Botswana Pula | ||

| Cape Town Stock Exchange | Cape Town | 2016 | South Africa Rand | ||

| Eswatini Stock Exchange | Mbabane | 1990 | Eswatini lilangeni | ||

| Johannesburg Stock Exchange Limited | Johannesburg | 1887 | South Africa Rand | ||

| Lusaka Stock Exchange | Lusaka | 1994 | Zambian Kwacha | ||

| Malawi Stock Exchange | Blantyre | 1996 | Malawi Kwacha | ||

| Namibian Stock Exchange | Windhoek | 1904 | Namibian Dollar | ||

| Victoria Falls Stock Exchange | Victoria Falls | 2020 | United States Dollar | ||

| Zimbabwe Stock Exchange | Harare | 1896 | Zimbabwe Dollar |

Between 2009 and 2012, a total of 72 companies were launched on the stock exchanges of 13 African countries.[205]

See also

[edit]- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

- Africa–China economic relations

- African Economic Community

- African Economic Outlook

- Demographics of Africa

- Economic history of Africa

- Economy of East Africa

- List of largest companies in Africa by revenue

- Land grabbing

- Languages of Africa

- List of countries by percentage of population living in poverty

- List of countries by Human Development Index

- Central banks and currencies of Africa

- List of countries by credit rating

- List of countries by future gross government debt

- List of countries by public debt

- List of countries by leading trade partners

- List of countries by industrial production growth rate

- List of countries by GDP (nominal)

- List of countries by GDP (nominal) per capita

- List of countries by GDP (PPP)

- List of countries by GDP (PPP) per capita

- List of countries by GNI (nominal) per capita

- List of countries by tax revenue as percentage of GDP

- List of countries by GDP growth

Citations

[edit]- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "GDP (Nominal), current prices". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "GDP (PPP), current prices". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ International Monetary Fund (2022). "Real GDP growth". IMF Data Mapper. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ International Monetary Fund (2022). "Nominal GDP per capita". IMF Data Mapper. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ International Monetary Fund (2022). "GDP PPP per capita". IMF Data Mapper. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ International Monetary Fund (2022). "Inflation rate, average consumer prices". IMF Data Mapper. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Shorrocks, Anthony; Davies, James; Lluberas, Rodrigo (2022). Global Wealth Databook 2022 (PDF). Credit Suisse Research Institute.

- ^ International Monetary Fund (2022). "General government gross debt". IMF Data Mapper. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "2017 World population" (PDF). 2017 World Population Data Sheet – Population Reference Bureau.

- ^ a b c "Overview".

- ^ Veselinovic, Milena. "Why is Africa so unequal?". CNN. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Africa rising". The Economist. 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Get ready for an Africa boom". Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Despite Global Slowdown, African Economies Growing Strongly― New Oil, Gas, and Mineral Wealth an Opportunity for Inclusive Development". World Bank. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Anyangwe, Eliza (28 June 2017). "Why is Africa so poor? You asked Google – here's the answer". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Oliver August (2 March 2013). "Africa rising A hopeful continent". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/AFQ/DZA/ZAF/MAR/NGA/EGY?year=2018.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Rise of the African opportunity". Boston Analytics. 22 June 2016.

- ^ "European Trade, Colonialism, and Human Capital Accumulation in Senegal, Gambia and Western Mali, 1770–1900 – African Economic History Network". www.aehnetwork.org. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Baten, Jörg; Alexopoulou, Kleoniki. "Elite violence and elite numeracy in Africa from 1400 CE to 1950 CE".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ocran, Matthew Kofi (2019), Ocran, Matthew Kofi (ed.), "Post-Independence African Economies: 1960–2015", Economic Development in the Twenty-first Century: Lessons for Africa Throughout History, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 301–372, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-10770-3_9, ISBN 978-3-030-10770-3, S2CID 159395862, retrieved 7 July 2021

- ^ "Africa rising". The Economist. 3 December 2011. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Africa calling". Financial Times. 10 March 2013.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF.org. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ "Overview". World Bank. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Botswana – an African economic miracle?". LSE International Development. 28 January 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ a b World Economic Situation and Prospects 2018. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Development Policy and Analysis Division. 23 January 2018. p. 106. ISBN 978-92-1-109177-9. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "'Fast economic growth' in Africa". 14 November 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "African economy 'to expand 6.2%'". 13 June 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ a b Bank, European Investment (19 October 2022). Finance in Africa – Navigating the financial landscape in turbulent times. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5382-2.

- ^ Selassie, Abebe Aemro; Department, Shushanik Hakobyan IMF African. "Six Charts Show the Challenges Faced by Sub-Saharan Africa". IMF. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Africa's Rapid Economic Growth Hasn't Fully Closed Income Gaps". IMF. 21 September 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "African growth 'steady but frail'". BBC News. 3 April 2007.

- ^ "Lions on the move: The progress and potential of African economies". McKinsey & Company. June 2010. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative – Questions and Answers". www.imf.org. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Debt Relief Under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative". IMF. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d Bank, European Investment (18 November 2021). Finance in Africa: for green, smart and inclusive private sector development. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5063-0.

- ^ "Hundreds of African financial professionals benefit from EIB banking and microfinance academy". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Finance in Africa 2023". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "Finance in Africa 2023". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "Policy Responses to COVID19". IMF. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "World Economic Situation Prospects" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2021.

- ^ "The territorial impact of COVID-19: Managing the crisis and recovery across levels of government". OECD. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Finance in Africa: for green, smart and inclusive private sector development". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "The territorial impact of COVID-19: Managing the crisis and recovery across levels of government". OECD. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ "FAQs on ECB supervisory measures in reaction to the coronavirus". European Central Bank. 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Global Growth to Slow through 2023, Adding to Risk of 'Hard Landing' in Developing Economies". World Bank. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Country notes" (PDF). African Development Bank.

- ^ "Africa banks maintain resilience amid difficulty, EIB survey shows – Businessamlive". Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Bank, European Investment (27 September 2023). Finance in Africa: Uncertain times, resilient banks: African finance at a crossroads. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5598-7.

- ^ Blake, Jessica (12 April 2023). "Comment: Africa has the highest proportion of women entrepreneurs. How can we make sure they get funded?". Reuters. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "The Business Case for Investing in African Women – Women's World Banking". www.womensworldbanking.org. 15 December 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Liu, Yu; Wei, Siqi; Xu, Jian (November 2021). "COVID-19 and Women-Led Businesses around the World". Finance Research Letters. 43: 102012. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2021.102012. ISSN 1544-6123. PMC 8596885. PMID 34803532.

- ^ "COVID-19 Impacts on Women in Emerging Economies" (PDF).

- ^ Bank, European Investment (7 November 2024). Finance in Africa: Unlocking investment in an era of digital transformation and climate transition. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5767-7.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (7 November 2024). Finance in Africa: Unlocking investment in an era of digital transformation and climate transition. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5767-7.

- ^ "African Economic Outlook 2024".

- ^ Bank, European Investment (7 November 2024). Finance in Africa: Unlocking investment in an era of digital transformation and climate transition. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5767-7.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (7 November 2024). Finance in Africa: Unlocking investment in an era of digital transformation and climate transition. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5767-7.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (7 November 2024). Finance in Africa: Unlocking investment in an era of digital transformation and climate transition. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5767-7.

- ^ "Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: Trends and Prospects". trendsresearch.org. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ "UN trade and development".

- ^ Bank, European Investment (7 November 2024). Finance in Africa: Unlocking investment in an era of digital transformation and climate transition. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5767-7.

- ^ "Economic Report on Africa 2012" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). p. 44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Mike King (18 July 2012). "China-Africa Trade Booms". The Journal of Commerce. The JOC Group, Inc. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ a b Lund, Susan; Arend Van Wamelen (7 September 2012). "10 things you didn't know about the African economy". The Independent. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Olga Khazan (3 July 2013). "The three reasons why the US is so interested in Africa right now". Quartz. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "AfCFTA". Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ The Economist, The African Century, 28 March 2020.

- ^ a b The Economist, "The African century", 28 March 2020.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (6 July 2022). EIB Group Sustainability Report 2021. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5237-5.

- ^ "Climate change triggers mounting food insecurity, poverty and displacement in Africa". public.wmo.int. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Global warming: severe consequences for Africa". Africa Renewal. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Climate Change Is an Increasing Threat to Africa". United Nations Climate Change News. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Rathi, Akshat; Rao, Mythili (2 May 2024). "One Bank Is Turning Africa's Climate Vulnerability Into Opportunity". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Hyden, Goran (23 October 2007). "Governance and poverty reduction in Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (43): 16751–16756. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10416751H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700696104. PMC 2040419. PMID 17942700.

- ^ a b Lange, Matthew Keith (2004). The British colonial lineages of despotism and development (Thesis). OCLC 61140381. ProQuest 305225106.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, S. (1 November 2009). "Root Causes of African Underdevelopment". Journal of African Economies. 18 (5): 745–780. doi:10.1093/jae/ejp009.

- ^ Awojobi, Oladayo Nathaniel (October 2014). "CORRUPTION AND UNDERDEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA: A DISCOURSE APPROACH" (PDF). International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management. 2 (10).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Christian K.M. Kingombe 2011. Mapping the new infrastructure financing landscape Archived 18 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ "Why is Africa so poor? You asked Google – here's the answer". the Guardian. 28 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Nick Mead, "African Economic Outlook 2012", The Guardian, 28 May 2012.

- ^ Lewis H. Gann and Peter Duignan, The Burden of Empire: A Reappraisal of Western Colonialism South of the Sahara

- ^ D. K. Fieldhouse, The West and the Third World

- ^ Niall Ferguson, Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World and Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire

- ^ http://pure.au.dk/portal-asb-student/files/41656700/alexandra_hrituleac_thesis_1_dec.pdf Archived 13 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ 1997: Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Co. (ISBN 978-0-099-30278-0). Also published with the title Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years.

- ^ James M. Blaut (2000). Eight Eurocentric Historians (10 August 2000 ed.). The Guilford Press. p. 228. ISBN 1-57230-591-6. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ Africa and Africans in the Formation of the Atlantic World, 1400–1680 (New York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1992, second expanded edition, 1998).

- ^ Why is Africa Poor? (Economic History of Developing Regions Vol. 25: 2010)

- ^ Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, 1972.

- ^ David Eltis, Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- ^ "Summary by country". Ethnologue. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ See, for example, Frank, A. G. (1979), Dependent Accumulation and Underdevelopment, New York: Monthly Review Press.; Köhler, G., and A. Tausch (2001), Global Keynesianism: unequal exchange and global exploitation, Nova Publishers; Amin, S. (1976), Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism, New York: Monthly Review Press.

- ^ Shaw, Jane (April 2004). "Overlooking the Obvious in Africa" (PDF). Econ Journal Watch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^ Pasour, E.C. (April 2004). "Intellectual Tyranny of the Status Quo" (PDF). Econ Journal Watch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^ Wrong, Michela (14 March 2005). "When the money goes west". New Statesman. Retrieved 28 August 2006.

- ^ "Should Africa challenge its "odious debts?"". Reuters. 15 March 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (20 October 2011). "Mobutu Sese Seko". Time. Top 15 Toppled Dictators. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011.

- ^ "How US nurtured dictators to Africa's detriment". Independent Online. 2 November 2018.

- ^ "The costs of the Robert Mugabe era". Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Skinner, Annabel (2005). Tanzania & Zanzibar. New Holland Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 1-86011-216-1.

- ^ "Download entire World Economic Outlook database, October 2017". www.imf.org. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Moyo, Dambisa (21 March 2009). "Why Foreign Aid Is Hurting Africa". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Moyo, Dambisa (26 March 2009). "Stop Aiding Africa!". Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "African Action Plan". UN Economic Commission for Africa. May 2003.

- ^ "Profile: African Union". BBC News. 1 July 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- ^ Sarl, ed. (2013). "2013 Guide economique du continentBourses Africaines". Africa 24 (8): 60.

- ^ Sarl, ed. (2013). "2013 Guide economique du continentBourses Africaines". Africa 24 (8): 62.

- ^ Luce and Agarwal (22 June 2016). "Rise of the African Opportunity". Boston Analytics. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ Sarl, ed. (2013). "2013 Guide economique du continentBourses Africaines". Africa 24 (8): 64–65.

- ^ a b "Economic Outlook". African Economic Outlook. 28 May 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ "African Economic Outlook 2011". Oecd.org. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Landry, Zainab Usman, David; Landry, Zainab Usman, David. "Economic Diversification in Africa: How and Why It Matters". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Economic Report on Africa 2012" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). p. 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Economic Report on Africa 2012" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). p. 46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Economic Report on Africa 2012" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). p. 47. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Based on the IMF data. If no data was available for a country from IMF, data from the World Bank is used.

- ^ a b "Global Wind Atlas". Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ a b c "World Economic Outlook Database, Octobre 2020". IMF. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ Source Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2005

- ^ a b Eurostat. "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by NUTS 2 regions". Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ a b CEROM. "Comptes économiques rapides de La Réunion en 2019" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ INSEE. "Figure 1 – Le PIB progresse de 2,2 % en volume en 2019" (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "... dévoile ses propositions locales. "Enfin !"". 1 December 2006.

- ^ https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/wp-09-02.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c d e f John J. Saul and Colin Leys, Sub-Saharan Africa in Global Capitalism, Monthly Review, 1999, Volume 51, Issue 03 (July–August)

- ^ a b c d e f Fred Magdoff, Twenty-First-Century Land Grabs: Accumulation by Agricultural Dispossession, Monthly Review, 2013, Volume 65, Issue 06 (November)

- ^ World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023 | FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2023. doi:10.4060/cc8166en. ISBN 978-92-5-138262-2. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Caplan, Gerald (2008). The Betrayal of Africa. Groundwood Books. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-88899-825-5.

- ^ Patel, Raj (2007). Stuffed and Starved. UK: Portobello Books. p. 57.

- ^ Agricultural Subsidies in the WTO Green Box Archived 12 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, ICTSD, September 2009.

- ^ "Agricultural Subsidies, Poverty and the Environment" (PDF). World Resources Institute. January 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "How much does it hurt? The Impact of Agricultural Trade Policies on Developing Countries" (PDF). IFPRI. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Farm Subsidies: Devastating the World's Poor and the Environment". www.ncpa.org. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Inter Press Service | News and Views from the Global South". ipsnews.net. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Hareyan, Armine (1 December 2008). "Targeted agricultural investments will slash poverty in Africa". HULIQ. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Redirecting". africanagriculture.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Usman, Talatu (30 January 2014). "Private sector invests N1.7 trillion in Nigeria's agricultural sector – Jonathan". Premium Times. Nigeria. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "South Africa: Commodities lead boom".

- ^ "Yara's GroHow sees 2008 profit stable". Reuters. 22 February 2008.

- ^ "Govt targets agricultural boom – Daily Monitor". Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ SciDev.Net. "African Union support crucial for agricultural progress". SciDev.Net. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Section, United Nations News Service (9 May 2008). "Though making 'very good progress,' Africa still faces challenges, says UN official". UN News Service Section. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Agaba, John (2 May 2022). "African researchers: Tick vaccines can stop use of dangerous pesticides". Alliance for Science. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Sarl, Etnium, ed. (2013). "2013 Guide economique du continent Bourses Africaines". Africa 24 Magazine (8): 12–13. ISSN 2114-2610.

- ^ "Table 7 – Exports, 2010". African Economic Outlook. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "As Africa looks for clean power, interest in nuclear grows". The Japan Times. 10 April 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ a b Sarl, ed. (2013). "2013 Guide economique du continent Bourses Africaines". Africa 24 (8): 20–21.

- ^ Jedwab, Remi; Storeygard, Adam (4 May 2019). "Economic and Political Factors in Infrastructure Investment: Evidence from Railroads and Roads in Africa 1960–2015". Economic History of Developing Regions. 34 (2): 156–208. doi:10.1080/20780389.2019.1627190. S2CID 199535355.

- ^ Sarl, ed. (2013). "2013 Guide economique du continent Bourses Africaines". Africa 24 (8): 24.

- ^ a b "Yesterday mineral supplier, tomorrow battery producer - The Nordic Africa Institute". nai.uu.se. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ African Mining Vision (AMV). "The African Union (AU)".

- ^ "Africa strives to rebuild its domestic industries".

- ^ "technology | IOL Business Report". Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Resources Boom Represents Development Potential in Africa – Mining Technology". www.mining-technology.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Grobler, John (16 October 2008). "Namibia: Congo Copper Giant to Invest in Country". The Namibian (Windhoek). Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Tax breaks for big investment projects". southafrica.info.

- ^ "ECONOMY-MAURITIUS: Textile Manufacturing Goes Green and Clean". Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ "Market for renewable energy expected to boom in Africa". Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ "Alternative Energy Africa". ae-africa.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Innoson cars will sell for N1 million in 2014 – Chukwuma". The Abuja Inquirer. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Local vehicles manufacturing – INNOSON/FG pact commendable". Vanguard Newspapers. Vanguard. 19 October 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "CHUKWUMA: BUSINESSMAN WHO DEFIED THE LIMITS". The Nigerian Voice. NBF News. 25 February 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Obaze, Oseloka H. (12 December 2013). "Innoson Vehicle Manufacturing granted license to export its vehicles". Elombah. Elombah.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "I Couldn't Meet Cut-off Mark to Study Engineering – Innoson". This Day Newspaper. This Day Live. 1 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Okonji, Emma (24 October 2013). "Zinox Introduces Tablet Range of Computers, Plans Commercial Launch". This Day. This Day Live. Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Onuba, Ifeanyi (4 October 2014). "FG raises tariff on imported cars". Punch Newspaper. Punch NG. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Clement, Udeme (19 January 2014). "Will the new automotive policy give us affordable made-in-Nigeria car?". Vanguard. Vanguard Nigeria. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Agande, Ben (24 January 2014). "Nissan to role out 1st made in Nigeria cars in April". Vanguard, Nigeria. Vanguard. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Awe, Olumide; Sholotan, Olugbenga; Asaolu, Olubunmi (5 June 2010). "Consumer goods businesses to do well in Nigeria". Trade Invest. Trade Invest Nigeria. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Orya Roberts (29 December 2013). "'Revamping Nigeria's manufacturing sector'". Sunday Trust. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "Welcome to Nigeria Pharma Manufactures Expo 2013..!". Nigeria Pharmaceutical Manufacturers. Nigeria Pharma Manufacturer Expo 2013. 19 October 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Anudu, Odinaka (27 November 2013). "Nigeria overtakes South Africa as biggest cement manufacturer in SSA". Business Day. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "Aliko Dangote Launches Nigeria's biggest cement plant". Elombah. Elombah.com. 11 June 2012. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "Industrial hub: Why more companies are moving to Ogun". Vanguard Nigeria. 19 June 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Ogun State's rising investment profile". Daily NewsWatch. 5 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Ogun State: Nigeria's new Industrial hub". Online Nigeria News. 27 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b African Development Bank (2014). Eastern Africa' manufacturing sector: Promoting technology, innovation, productivity and linkages (PDF).

- ^ Calabrese, Linda (March 2017). "How manufacturing motorcycles can boost Uganda's economy". ODI. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Africa's banking industry set for impressive growth: study". The China Post. 8 March 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Geoffrey Muzigiti; Oliver Schmidt (January 2013). "Moving forward". D+C Development and Cooperation/ dandc.eu.

- ^ "India to Step Up Trade and Investment in Africa".

- ^ "China in Africa: Friend or foe?". 26 November 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Chinese investment in Africa soars". Worldfocus. 13 October 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "China to maintain aid, investment in Africa 'regardless of financial crisis'". Xinhuanet. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009.

- ^ "China outwits the EU in Africa". Asia Time. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2017.