Achill Island

Native name: Acaill, Oileán Acla | |

|---|---|

Topography of Achill | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 53°57′50″N 10°00′11″W / 53.964°N 10.003°W |

| Archipelago | Achill |

| Total islands | 3 (Achill, Innisbiggle and Achillbeg islands) |

| Major islands | Achill |

| Area | 36,572 acres (14,800 ha) |

| Coastline | 128 km (79.5 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 688 m (2257 ft) |

| Highest point | Croaghaun |

| Administration | |

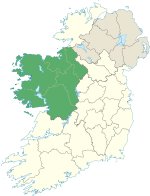

| Province | Connacht |

| County | Mayo |

| Barony | Burrishoole |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2,345 (2022)[1] |

| Pop. density | 17.3/km2 (44.8/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Irish |

| Additional information | |

| Ireland's largest island | |

Achill Island (/ˈækəl/; Irish: Acaill, Oileán Acla) is an island off the west coast of Ireland in the historical barony of Burrishoole, County Mayo. It is the largest of the Irish isles and has an area of approximately 148 km2 (57 sq mi). Achill had a population of 2,345 in the 2022 census.[1] The island, which has been connected to the mainland by a bridge since 1887, is served by Michael Davitt Bridge, between the villages of Achill Sound and Polranny. Other centres of population include the villages of Keel, Dooagh, Dooega, Dooniver, and Dugort. There are a number of peat bogs on the island.[2]

Roughly half of the island, including the villages of Achill Sound and Bun an Churraigh, are in the Gaeltacht (traditional Irish-speaking region) of Ireland,[3] although the vast majority of the island's population speaks English as their daily language.[citation needed]

The island is within a civil parish, also called Achill, that includes Achillbeg, Inishbiggle and the Corraun Peninsula.

History

[edit]It is believed that at the end of the Neolithic Period (around 4000 BC), Achill had a population of 500–1,000 people. The island was mostly forest until the Neolithic people began crop cultivation. Settlement increased during the Iron Age, and the dispersal of small promontory forts around the coast indicate the warlike nature of the times. Megalithic tombs and forts can be seen at Slievemore, along the Atlantic Drive and on Achillbeg.[4]

Overlords

[edit]Achill Island lies in the historical barony of Burrishoole, in the territory of ancient Umhall (Umhall Uactarach and Umhall Ioctarach), that originally encompassed an area extending from the County Galway/Mayo border to Achill Head.

The hereditary chieftains of Umhall were the O'Malleys, recorded in the area in 814 AD when they successfully repelled an incursion by Viking attackers in Clew Bay. The Anglo-Norman invasion of Connacht in 1235 AD saw the territory of Umhall taken over by the Butlers and later by the de Burgos. The Butler Lordship of Burrishoole continued into the late 14th century when Thomas le Botiller was recorded as being in possession of Akkyll and Owyll.[4]

Immigration

[edit]In the 17th and 18th centuries, there was migration to Achill from other parts of Ireland, including from Ulster, due to the political and religious turmoil of the time. For a period, there were two different dialects of Irish being spoken on Achill. This led to several townlands being recorded as having two names during the 1824 Ordnance Survey, and some maps today give different names for the same place. Achill Irish still has some traces of Ulster Irish.[citation needed] In the 19th and early 20th centuries, seasonal migration of farm workers to East Lothian to pick potatoes took place; these groups of 'tattie howkers' were known as Achill workers, although not all were from Achill, and were organised for potato merchants by gaffers or gangers.[5] Groups travelled from farm to farm to harvest the crop and were allocated basic accommodation. On 15 September 1937, ten young migrant potato pickers from Achill died in a fire at Kirkintilloch in Scotland.[6][7]

Achill was connected to the mainland by Michael Davitt Bridge, a bridge connecting the of Achill Sound and Polranny, in 1887.

Specific historical sites and events

[edit]Grace O'Malley's Castle

[edit]Carrickkildavnet Castle is a 15th-century tower house associated with the O'Malley Clan, who were once a ruling family of Achill. Grace O' Malley, or Granuaile, the most famous of the O'Malleys, was born on Clare Island around 1530.[8] Her father was the chieftain of the barony of Murrisk. The O'Malleys were a powerful seafaring family, who traded widely. Grace became a fearless leader and gained fame as a sea captain and pirate. She is reputed to have met Queen Elizabeth I in 1593. She died around 1603 and is buried in the O'Malley family tomb on Clare Island.

Achill Mission

[edit]

The Achill Mission, also known as 'the Colony' at Dugort, was founded in 1831 by the Anglican (Church of Ireland) Rev Edward Nangle. The mission included schools, cottages, an orphanage, an infirmary and a guesthouse.[9]

The Colony gave rise to mixed assessments, particularly during the Great Famine when charges of "souperism" were leveled against Nangle.[10] The provision of food across the Achill Mission schools - which also provided 'scriptural' religious instruction - was particularly controversial.[11]

For almost forty years, Nangle edited a newspaper called the Achill Missionary Herald and Western Witness, which was printed in Achill. He expanded his mission into Mweelin, Kilgeever, West Achill where a school, church, rectory, cottages and a training school were built. Edward's wife, Eliza, suffered poor health in Achill and died in 1852; she is buried with six of the Nangle children on the slopes of Slievemore in North Achill.[12]

In 1848, at the height of the Great Famine, the Achill Mission published a prospectus seeking to raise funds for the acquisition of significant additional lands from Sir Richard O'Donnell. The document gives an overview, from the Mission's perspective, of its activities in Achill over the previous decade and a half including considerable sectarian unrest.[13] In 1851, Edward Nangle confirmed the purchase of the land which made the Achill Mission the largest landowner on the island.

The Achill Mission began to decline slowly after Nangle was moved from Achill and it closed in the 1880s. When Edward Nangle died in 1883 there were opposing views on his legacy.[14]

Railway

[edit]In 1894, the Westport – Newport railway line was extended to Achill Sound. The railway station is now a hostel. The train provided a great service to Achill, but it also is said to have fulfilled an ancient prophecy. Brian Rua O' Cearbhain had prophesied that 'carts on iron wheels' would carry bodies into Achill on their first and last journey. In 1894, the first train on the Achill railway carried the bodies of victims of the Clew Bay Drowning. This tragedy occurred when a boat overturned in Clew Bay, drowning thirty-two young people. They had been going to meet the steamer SS Elm[15] which would take them to Britain for potato picking.[16]

The Kirkintilloch Fire in 1937 almost fulfilled the second part of the prophecy when the bodies of ten victims were carried by rail to Achill. While it was not literally the last train, the railway closed just two weeks later. These people had died in a fire in a bothy in Kirkintilloch. This term referred to the temporary accommodation provided for those who went to Scotland to pick potatoes, a migratory pattern that had been established in the early nineteenth century.[17]

Kildamhnait

[edit]Kildamhnait on the south-east coast of Achill is named after St. Damhnait, or Dymphna, who founded a church there in the 7th century.[18] There is also a holy well just outside the graveyard. The present church was built in the 1700s and the graveyard contains memorials to the victims of two of Achill's greatest tragedies, the Kirchintilloch Fire (1937) and the Clew Bay Drowning (1894).

The Monastery

[edit]In 1852, John MacHale, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Tuam, purchased land in Bunnacurry, on which a Franciscan Monastery was established, which, for many years, provided an education for local children. The building of the monastery was marked by a conflict between the Protestants of the mission colony and the workers building the monastery. The dispute is known in the island folklore as the Battle of the Stones.[19]

A monk who lived at the monastery for almost thirty years was Paul Carney. He wrote a biography of James Lynchehaun who was convicted for the 1894 attack on an Englishwoman named Agnes MacDonnell, which left her face disfigured, and the burning of her home, Valley House, Tonatanvally, North Achill. The home was rebuilt and MacDonnell died there in 1923, while Lynchehaun escaped to the US after serving 7 years and successfully resisted extradition but spent his last years in Scotland, where he died. Carney's great-grandniece, Patricia Byrne, wrote her own account of Mrs MacDonnell and Lynchehaun, entitled The Veiled Woman of Achill.[20]

Carney also wrote accounts of his lengthy fundraising trips across the U.S. at the start of the 20th century.[21] The ruins of this monastery are still to be seen in Bunnacurry today.

Valley House

[edit]The historic Valley House is located in Tonatanvally, "The Valley", near Dugort, in the northeast of Achill Island. The present building sits on the site of a hunting lodge built by the Earl of Cavan in the 19th century. Its notoriety arises from an incident in 1894 in which the then owner, an Englishwoman, Mrs Agnes McDonnell, was savagely beaten and the house set alight by a local man, James Lynchehaun. Lynchehaun had been employed by McDonnell as her land agent, but the two fell out and he was sacked and told to quit his accommodation on her estate. A lengthy legal battle ensued, with Lynchehaun refusing to leave. At the time, in the 1890s, the issue of land ownership in Ireland was politically charged. After the events at the Valley House in 1895, Lynchehaun would falsely claim his actions were carried out on behalf of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and motivated by politics. He escaped from custody after serving seven years[22] and fled to the United States seeking political asylum (although Michael Davitt refused to shake his hand, calling Lynchehaun a "murderer"), where he successfully defeated legal attempts by the British authorities to have him extradited to face charges arising from the attack and the burning of the Valley House. Agnes McDonnell suffered terrible injuries from the attack but survived and lived for another 23 years, dying in 1923. Lynchehaun is said to have returned to Achill on two occasions, once in disguise as an American tourist, and eventually died in Girvan, Scotland, in 1937. The Valley House is now a hostel and bar.[23]

Deserted Village

[edit]Close to Dugort, at the base of Slievemore mountain lies the Deserted Village. There are approximately 80 ruined houses in the village. The houses were built of unmortared stone. Each house consisted of just one room. In the area surrounding the Deserted Village, including on the mountain slopes, there is evidence of 'lazy beds' in which crops like potatoes were grown. In Achill, as in other areas of Ireland, a 'rundale' system was used for farming. This meant that the land around a village was rented from a landlord. This land was then shared by all the villagers to graze their cattle and sheep. Each family would then have two or three small pieces of land scattered about the village, which they used to grow crops. For many years people lived in the village and then in 1845 famine struck in Achill as it did in the rest of Ireland. Most of the families moved to the nearby village of Dooagh, which is beside the sea, while others emigrated. Living beside the sea meant that fish and shellfish could be used for food. The village was completely abandoned and is now known as the 'Deserted Village'.[citation needed]

While abandoned, the families that moved to Dooagh (and their descendants) continued to use the village as a 'booley village'.[24] This means that during the summer season, the younger members of the family, teenage boys and girls, would take the livestock to the area and tend flocks or herds on the hillside and stay in the houses of the Deserted Village. They would then return to Dooagh in the autumn. This custom continued until the 1940s. Boolying was also carried out in other areas of Achill, including Annagh on Croaghaun mountain and in Curraun. At Ailt, Kildownet, the remains of a similar deserted village can be found. This village was deserted in 1855 when the tenants were evicted by the local landlord so the land could be used for cattle grazing; the tenants were forced to rent holdings in Currane, Dooega and Slievemore. Others emigrated to America.[citation needed]

Archaeology

[edit]

In 2009, a summer field school excavated Round House 2 on Slievemore Mountain under the direction of archaeologist Stuart Rathbone. Only the outside north wall, entrance way and inside of the Round House were completely excavated.[25]

From 2004 to 2006, the Achill Island Maritime Archaeology Project directed by Chuck Meide was sponsored by the College of William and Mary, the Institute of Maritime History, the Achill Folklife Centre (now the Achill Archaeology Centre), and the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP). This project focused on the documentation of archaeological resources related to Achill's rich maritime heritage. Maritime archaeologists recorded a 19th-century fishing station, an ice house, boat house ruins, a number of anchors which had been salvaged from the sea, 19th-century and more recent currach pens, a number of traditional vernacular watercraft including a possibly 100-year-old Achill yawl, and the remains of four historic shipwrecks.[26][27]

A number of the oldest inhabited cottages in the area date from the activities of the Congested Districts Board for Ireland—a body set up around the turn of the 20th century in Ireland to improve the welfare of the inhabitants of small villages and towns. Many of the homes in Achill at the time were very small and tightly packed together in villages. The Congested Districts Board for Ireland (CDB) subsidised the building of new, more spacious (though still small by modern standards) homes outside of the traditional villages.[citation needed]

Other places of interest

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

The cliffs of Croaghaun on the western end of the island are the third highest sea cliffs in Europe but are inaccessible by road. Near the westernmost point of Achill, Achill Head, is Keem Bay. Keel Beach is visited by tourists and used as a surfing location.[citation needed] South of Keem beach is Moytoge Head, which with its rounded appearance drops dramatically down to the ocean. An old British observation post, built during World War I to prevent the Germans from landing arms for the Irish Republican Army, still stands on Moytoge. During the Emergency (WWII), this post was rebuilt by the Irish Defence Forces as a lookout post for the Coast Watching Service wing of the Defence Forces. It operated from 1939 to 1945.[28]

The mountain of Slievemore, (672 m) rises dramatically in the north of the island. On its slops is an abandoned village, the "Deserted Village". West of this ruined village is an old Martello tower, again built by the British to warn of any possible French invasion during the Napoleonic Wars. The area also has an approximately 5000-year-old Neolithic tomb.

Achillbeg (Acaill Beag, Little Achill) is a small island just off Achill's southern tip. Its inhabitants were resettled on Achill in the 1960s.[29] A plaque to the boxer Johnny Kilbane is situated on Achillbeg and was erected to celebrate 100 years since his first championship win.[30]

Caisleán Ghráinne, also known as Kildownet Castle, is a small tower house built in the early 1400s.[31] It is located in Cloughmore, on the south of Achill Island. It is noted for its associations with Grace O'Malley, along with the larger Rockfleet Castle in Newport.

Economy and tourism

[edit]While a number of attempts at setting up small industrial units on the island have been made, its economy is largely dependent on tourism. Subventions from Achill people working abroad allowed a number of families to remain living in Achill throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.[citation needed] In the past, fishing was a significant activity but this aspect of the economy has since reduced. At one stage, the island was known for its shark fishing, and basking shark in particular was fished for its valuable shark liver oil.

During the 1960s and 1970s, there was growth in tourism. The largest employers on Achill include its two hotels.[32] The island has several bars, cafes and restaurants. The island's Atlantic location means that seafood, including lobster, mussels, salmon, trout and winkles, are common. Lamb and beef are also popular.[33]

Religion

[edit]Most people on Achill are either Roman Catholic or Anglican (Church of Ireland).[citation needed]

Catholic churches on the island include: Bunnacurry Church (Saint Josephs), The Valley Church (only open for certain events), Pollagh Church, Dooega Church and Achill Sound Church.[citation needed]

There is a Church of Ireland church (St. Thomas's church) at Dugort.[citation needed]

The House of Prayer, a controversial "religious retreat" on the island,[34][35] was established in 1993.[36]

Artists

[edit]For almost two centuries, a number of artists have had a close relationship with Achill Island, including the landscape painter Paul Henry.[37] Within the emerging Irish Free State, Paul Henry's landscapes from Achill and other areas reinforced a vision of Ireland of communities living in harmony with the land.[38] He lived in Achill for almost a decade with his wife, artist Grace Henry and, while using similar subject-matter, the pair developed very different styles.[39]

This relationship of artists with Achill was particularly intense in the early decades of the twentieth century when Eva O'Flaherty (1874–1963) became a focal point for artistic networking on the island.[40] A network of over 200 artists linked to Achill is charted in "Achill Painters - An Island History" and includes painters such as the Belgian Marie Howet, the American Robert Henri, the modernist painter Mainie Jellett and contemporary artist Camille Souter.[41]

The 2018 Coming Home Art & The Great Hunger exhibition,[42] in partnership with The Great Hunger Museum of Quinnipiac University, USA, featured Achill's Deserted Village and the island lazy beds prominently in works by Geraldine O'Reilly and Alanna O'Kelly; also included was an 1873 painting, 'Cottage, Achill Island' by Alexander Williams - one of the first artists to open up the island to a wider audience.[43]

Education

[edit]Hedge schools existed in most villages of Achill in various periods of history. A university was started by the missions to Achill in Mweelin.

At the turn of the 21st century there were two secondary schools in Achill: Mc Hale College and Scoil Damhnait. These two schools amalgamated, in 2011, to form Coláiste Pobail Acla.

For primary education, there are eight national schools. These including Bullsmouth NS, Valley NS, Bunnacurry NS, Dookinella NS, Dooagh NS, Saula NS, Achill Sound NS and Tonragee NS.[citation needed]

Transport

[edit]

Rail

[edit]Achill railway station, still on the mainland and not on the island, was opened by the Midland Great Western Railway on 13 May 1895, the terminus of its line from Westport via Newport and Mulranny. The station, and the line, were closed by the Great Southern Railways on 1 October 1937.[44] The Great Western Greenway, created during 2010 and 2011, follows the line's route[45] and has proved to be very successful in attracting visitors to Achill and the surrounding areas.

Road

[edit]The R319 road is the main road onto the island.[46]

Bus Éireann's route 450 operates several times daily to Westport and Louisburgh from the island. Bus Éireann also provides transport for the area's secondary school children.[citation needed]

Sport

[edit]Achill has a Gaelic football club which competes in the junior championship and division 1E of the Mayo League. There are also Achill Rovers which play in the Mayo Association Football League.[47]

There is a 9-hole links golf course on the island.[48] Outdoor activities can be done through Achill Outdoor Education Centre.[49] Achill Island's rugged landscape and the surrounding ocean offers multiple locations for outdoor adventure activities, like surfing, kite-surfing and sea kayaking. Fishing and watersports are also common.[citation needed] Sailing regattas featuring a local vessel type, the Achill Yawl, have been run since the 19th century.[citation needed]

Demographics

[edit]In 2016, the population was 2,594,[50] with 5.2% claiming they spoke Irish on a daily basis outside the education system.[51] The island's population has declined from around 6,000 before the Great Famine of the mid-19th century.

The table below reports data on Achill Island's population taken from Discover the Islands of Ireland (Alex Ritsema, Collins Press, 1999) and the census of Ireland.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: Central Statistics Office. "CNA17: Population by Off Shore Island, Sex and Year". CSO.ie. Retrieved 12 October 2016. Population of Inhabited Islands Off the Coast (Report). Central Statistics Office. 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notable people

[edit]- Heinrich Böll, German writer who spent several summers with his family and later lived several months per year on the island

- Charles Boycott (1832–1897), unpopular landowner from whom the term boycott arose

- Nancy Corrigan, pioneer aviator, second female commercial pilot in the US.

- Dermot Freyer (1883–1970), writer who opened a hotel on the island

- Paul Henry, artist, stayed on the island for a number of years in the early 1900s

- James Kilbane, singer, lives on the island

- Johnny Kilbane, boxer

- Saoirse McHugh, former Green Party politician

- Danny McNamara, musician

- Richard McNamara, musician

- Eva O'Flaherty, Nationalist, model and milliner

- Thomas Patten, from Dooega. Died during the Siege of Madrid in December 1936

- Honor Tracy, author, lived there until her death in 1989

In popular culture

[edit]The island is featured throughout the film The Banshees of Inisherin in various locations on the island including Keem Bay, Cloughmore, and Purteen Pier.[52]

The island is also the primary setting of the visual novel If Found....[citation needed]

Further reading

[edit]- Heinrich Böll: Irisches Tagebuch, Berlin, 1957

- Bob Kingston The Deserted Village at Slievemore, Castlebar, 1990

- Theresa McDonald: Achill: 5000 B.C. to 1900 A.D.: Archeology History Folklore, I.A.S. Publications [1992]

- Rosa Meehan: The Story of Mayo, Castlebar, 2003

- James Carney: The Playboy & the Yellow lady, 1986 Poolbeg[53]

- Hugo Hamilton: The Island of Talking,[54] 2007

- Mealla Nī Ghiobúin: Dugort, Achill Island 1831–1861: The Rise and Fall of a Missionary Community, 2001

- Patricia Byrne: The Veiled Woman of Achill – Island Outrage & A Playboy Drama, 2012

- Mary J. Murphy: Achill's Eva O'Flaherty – Forgotten Island Heroine, 2011

- Patricia Byrne: The Preacher and The Prelate – The Achill Mission Colony and The Battle for Souls in Famine Ireland, 2018

- Mary J. Murphy, Achill Painters -An Island History, 2020

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Population of Inhabited Islands Off the Coast (Report). Central Statistics Office. 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "The Natural World - Achill Tourism". Achill Tourism. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "Gaeltacht Boundaries Generalised to 50m". census2016.geohive.ie. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ a b McDonald, Theresa (2006). Achill Island: Archeology, History, Folklore. Tullamore, Co. Offaly, Ireland: I.A.S. Publications. pp. 1–6. ISBN 0951997416.

- ^ Holmes, Heather (2000). 'As good as a holiday': Potato harvesting in the Lothians from 1870 to the present. East Linton, East Lothian: Tuckwell. pp. 185–219.

- ^ "The Kirkintilloch Tragedy, 1937 – The Irish Story". Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ "Kirkintilloch Disaster". RTÉ Archives. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Lynch, Peter (20 June 2016). "The Pirate Queen of County Mayo". BBC. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Ni Ghiobuin, Mealla C (2001). Dugort, Achill Island 1831–1861. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. pp. 7–21. ISBN 0716527405.

- ^ Kinealy, Christine (2002). The Great Irish Famine: Impact, Ideology and Rebellion. New York: Palgrave. pp. 160–166. ISBN 9780333677735.

- ^ Byrne, Patricia (January 2022). "God's Scourge on a Sinful Nation: The Great Famine from an Achill Mission Perspective". Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society. 73: 29–30.

- ^ Byrne, Patricia (25 February 2020). "A controversial Mission". The Irish Times.

- ^ Byrne, Patricia (2022). "Evangelical Mission Pivots to Landlord in Famine Achill". History Ireland. 30 (4): 28–31.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Byrne, Patricia. "Weapons of his own forging: Edward nangle, Controversial in Life and in Death". The Irish Story. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "32 Achill People Drowned at Westport Quay". achilltourism.com. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Byrne, Patricia (2012). The Veiled Woman of Achill. Cork: The Collins Press. pp. 6–15. ISBN 9781848891470.

- ^ Coughlan, Brian (2006). Achill Island, tattie hokers in Scotland and the Kirkintilloch tragedy 1937. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781846820038.

- ^ "An Irishman's Diary". The Irish Times. Dublin. 17 June 2002. ISSN 0791-5144. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Joyce, P.J. (1910). A Forgotten Part of Ireland. Tuam, Ireland. pp. 148.

- ^ "Assault on Achill", irishtimes.com. Accessed 27 October 2022.

- ^ Byrne, Patricia (2009). "Teller of Tales: An Insight into the Life and Times of Brother Paul Carney (1844–1928), Travelling 'Quester' and Chronicler of the Life of James Lynchehaun, nineteenth-century Achill Criminal". Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society. 61: 156–169.

- ^ Byrne, Patricia. "Today In Irish History – Caught! Fugitive Criminal Lynchehaun Arrested, 5 January 1895". Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Byrne, Patricia (2012). The Veiled Woman of Achill: Island Outrage and A Playboy Drama. Cork, Ireland: The Collins Press. ISBN 9781848891470.

- ^ Deserted village, Slievemore, Achill Island, achill247.com Retrieved on 17 February 2008.

- ^ Amanda Burt, member of Achill Field School, Summer 2009.

- ^ "Achill Island Maritime Archaeology Project | Institute of Maritime History". Maritimehistory.org. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ Meide Chuck (18 June 2014). "Meide, Chuck and Kathryn Sikes (2014) Manipulating the Maritime Cultural Landscape: Vernacular Boats and Economic Relations on Nineteenth-Century Achill Island, Ireland. Journal of Maritime History 9(1):115–141". Journal of Maritime Archaeology. 9: 115–141. doi:10.1007/s11457-013-9123-3. S2CID 161863374.

- ^ See Michael Kennedy, Guarding Neutral Ireland (Dublin, 2008), p. 50

- ^ Jonathan Beaumont (2005), Achillbeg: The Life of an Island; ISBN 0-85361-631-0

- ^ McNulty, Anton (12 June 2012). "Statue of former boxing champion unveiled". The Mayo News. Westport, Ireland. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ "Irish Castles-Grace O'Malley". mythandlegends.net. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "Achill Island (Co. Mayo)". Irelandbyways.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Achill Island". gotoireland.today. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "House of Prayer returns to profit as donations increase". 21 August 2015.

- ^ "Mayo religious retreat accused of 'spiritual injury' by relatives of elderly man". 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Man under 'spiritual dominance' when he donated €200,000 to House of Prayer, court told". The Irish Times.

- ^ Tourism, Achill (7 September 2021). "Artists Inspired by Achill". Achill Tourism. Archived from the original on 11 January 2002.

- ^ National Gallery of Ireland (2019). Shaping Ireland - Landscapes in Irish Art. Dublin: National Gallery Of Ireland. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-904288-76-3.

- ^ Steward, James Christen (1999). When Time Began to Rant and Rage - Figurative Painting from Twentieth-century ireland. London: Merrell Holberton. p. 68. ISBN 1-85894-059-1.

- ^ Murphy, Mary J (2012). Achill's Eva O'Flaherty - Forgotten Island Heroine. Ireland: Knockma Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9560749-1-1.

- ^ "Achill Painters - an Island History".

- ^ O'Sullivan, Niamh, ed. (2018). Coming Home: Art and the Great Hunger. Ireland: Ireland's Great Hunger Museum, Quinnipiac University, USA. pp. 172, 178. ISBN 978-0-9978374-8-3.

- ^ Byrne, Patricia (9 September 2021). "Book Review: Mary J. Murphy, Achill Painters - An Island History". The Irish Story – via www.theirishstory.com.

- ^ "Achill station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ^ "Home". Great Western Greenway. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "S.I. No. 54/2012 — Roads Act 1993 (Classification of Regional Roads) Order 2012". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "FAI Club Portal for Achill Rovers". Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ "Achill Golf Club". Discover Ireland. 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Dave Jordan. "Achill Outdoor".

- ^ "ArcGIS Web. Application". airomaps.nuim.ie. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "ArcGIS Web Application". census.cso.ie. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Niall (1 November 2022). "Exact Filming Locations of 'The Banshees of Inisherin' (Ultimate In-Depth Guide)". Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ James Carney (1986). The playboy & the yellow lady. Open Library. ISBN 9780905169828. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ Hamilton, Hugo (2007). "The Island of Talking". Irish Pages. 4 (2): 23–31. JSTOR 25469746.