Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln | |

|---|---|

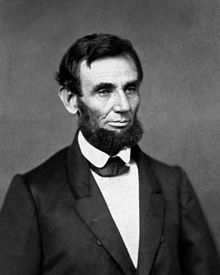

Lincoln in 1863 | |

| 16th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | James Buchanan |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 7th district | |

| In office March 4, 1847 – March 3, 1849 | |

| Preceded by | John Henry |

| Succeeded by | Thomas L. Harris |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from Sangamon County | |

| In office December 1, 1834 – December 4, 1842 | |

| Preceded by | Achilles Morris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 12, 1809 Sinking Spring Farm, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | April 15, 1865 (aged 56) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Manner of death | Assassination by gunshot |

| Resting place | Lincoln Tomb |

| Political party |

|

| Other political affiliations | National Union (1864–1865) |

| Height | 6 ft 4 in (193 cm)[1] |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Lincoln family |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Illinois Militia |

| Years of service | April–July 1832 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 31st (Sangamon) Regiment of Illinois Militia 4th Mounted Volunteer Regiment Iles Mounted Volunteers |

| Battles/wars |

|

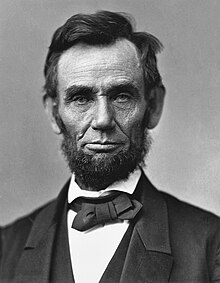

Abraham Lincoln (/ˈlɪŋkən/ LINK-ən; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War, defending the nation as a constitutional union, defeating the Confederacy, playing a major role in the abolition of slavery, expanding the power of the federal government, and modernizing the U.S. economy.

Lincoln was born into poverty in a log cabin in Kentucky and was raised on the frontier, mainly in Indiana. He was self-educated and became a lawyer, Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator, and U.S. representative from Illinois. In 1849, he returned to his successful law practice in Springfield, Illinois. In 1854, angered by the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which opened the territories to slavery, he re-entered politics. He soon became a leader of the new Republican Party. He reached a national audience in the 1858 Senate campaign debates against Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln ran for president in 1860, sweeping the North to gain victory. Pro-slavery elements in the South viewed his election as a threat to slavery, and Southern states began seceding from the nation. They formed the Confederate States of America, which began seizing federal military bases in the South. A little over one month after Lincoln assumed the presidency, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter, a U.S. fort in South Carolina. Following the bombardment, Lincoln mobilized forces to suppress the rebellion and restore the union.

Lincoln, a moderate Republican, had to navigate a contentious array of factions with friends and opponents from both the Democratic and Republican parties. His allies, the War Democrats and the Radical Republicans, demanded harsh treatment of the Southern Confederates. He managed the factions by exploiting their mutual enmity, carefully distributing political patronage, and by appealing to the American people. Anti-war Democrats (called "Copperheads") despised Lincoln, and some irreconcilable pro-Confederate elements went so far as to plot his assassination. His Gettysburg Address became one of the most famous speeches in American history. Lincoln closely supervised the strategy and tactics in the war effort, including the selection of generals, and implemented a naval blockade of the South's trade. He suspended habeas corpus in Maryland and elsewhere, and he averted war with Britain by defusing the Trent Affair. In 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the slaves in the states "in rebellion" to be free. It also directed the Army and Navy to "recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons" and to receive them "into the armed service of the United States." Lincoln pressured border states to outlaw slavery, and he promoted the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery, except as punishment for a crime. Lincoln managed his own successful re-election campaign. He sought to heal the war-torn nation through reconciliation. On April 14, 1865, just five days after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, he was attending a play at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., with his wife, Mary, when he was fatally shot by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth.

Lincoln is remembered as a martyr and a national hero for his wartime leadership and for his efforts to preserve the Union and abolish slavery. He is often ranked in both popular and scholarly polls as the greatest president in American history.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal Political 16th President of the United States First term Second term Presidential elections Speeches and works

Assassination and legacy  |

||

Family and childhood

Early life

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, the second child of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, in a log cabin on Sinking Spring Farm near Hodgenville, Kentucky.[2] He was a descendant of Samuel Lincoln, an Englishman who migrated from Hingham, Norfolk, to its namesake, Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1638. The family through subsequent generations migrated west, passing through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.[3] Lincoln was also a descendant of the Harrison family of Virginia; his paternal grandfather and namesake, Captain Abraham Lincoln and wife Bathsheba (née Herring) moved the family from Virginia to Jefferson County, Kentucky.[b] The captain was killed in an Indian raid in 1786.[5] His children, including eight-year-old Thomas, Abraham's father, witnessed the attack.[6][c] Thomas then worked at odd jobs in Kentucky and Tennessee before the family settled in Hardin County, Kentucky, in the early 1800s.[6]

Lincoln's mother Nancy Lincoln is widely assumed to be the daughter of Lucy Hanks.[8] Thomas and Nancy married on June 12, 1806, in Washington County, and moved to Elizabethtown, Kentucky.[9] They had three children: Sarah, Abraham, and Thomas, who died as an infant.[10]

Thomas Lincoln bought multiple farms in Kentucky, but could not get clear property titles to any, losing hundreds of acres of land in property disputes.[11] In 1816, the family moved to Indiana, where the land surveys and titles were more reliable.[12] They settled in an "unbroken forest"[13] in Hurricane Township, Perry County, Indiana.[14] When the Lincolns moved to Indiana it "had just been admitted to the Union" as a "free" (non-slaveholding) state,[15] except that, though "no new enslaved people were allowed, ... currently enslaved individuals remained so".[16][d] In 1860, Lincoln noted that the family's move to Indiana was "partly on account of slavery", but mainly due to land title difficulties.[18][19] In Kentucky and Indiana, Thomas worked as a farmer, cabinetmaker, and carpenter.[20] At various times he owned farms, livestock, and town lots, paid taxes, sat on juries, appraised estates, and served on county patrols. Thomas and Nancy were members of a Separate Baptist Church, which "condemned profanity, intoxication, gossip, horse racing, and dancing." Most of its members opposed slavery.[21]

Overcoming financial challenges, Thomas in 1827 obtained clear title to 80 acres (32 ha) in Indiana, an area that became known as Little Pigeon Creek Community.[22]

Mother's death

On October 5, 1818, Nancy Lincoln died from milk sickness, leaving 11-year-old Sarah in charge of a household including her father, nine-year-old Abraham, and Nancy's 19-year-old orphan cousin, Dennis Hanks.[23] Ten years later, on January 20, 1828, Sarah died while giving birth to a stillborn son, devastating Lincoln.[24]

On December 2, 1819, Thomas married Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow from Elizabethtown, Kentucky, with three children of her own.[25] Abraham became close to his stepmother and called her "Mother".[26] Dennis Hanks said he was lazy, for all his "reading—scribbling—writing—ciphering—writing poetry".[27] His stepmother acknowledged he did not enjoy "physical labor" but loved to read.[28][29]

Education and move to Illinois

Lincoln was largely self-educated.[30] His formal schooling was from itinerant teachers. It included two short stints in Kentucky, where he learned to read, but probably not to write. In Indiana at age seven,[31] due to farm chores, he attended school only sporadically, for a total of fewer than 12 months in aggregate by age 15.[32] Nonetheless, he remained an avid reader and retained a lifelong interest in learning.[33] Family, neighbors, and schoolmates recalled that his readings included the King James Bible, Aesop's Fables, John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, and The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin.[34] Despite being self-educated, Lincoln was the recipient of honorary degrees later in life, including an honorary Doctor of Laws from Columbia University in June 1861.[35]

When Lincoln was a teen, his "father grew more and more to depend on him for the 'farming, grubbing, hoeing, making fences' necessary to keep the family afloat. He also regularly hired his son out to work ... and by law, he was entitled to everything the boy earned until he came of age".[36] Lincoln was tall, strong, and athletic, and became adept at using an ax.[37] He was an active wrestler during his youth and trained in the rough catch-as-catch-can style (also known as catch wrestling). He became county wrestling champion at the age of 21.[38] He gained a reputation for his strength and audacity after winning a wrestling match with the renowned leader of ruffians known as the Clary's Grove boys.[39]

In March 1830, fearing another milk sickness outbreak, several members of the extended Lincoln family, including Abraham, moved west to Illinois, a free state, and settled in Macon County.[40][e] Abraham then became increasingly distant from Thomas, in part, due to his father's lack of interest in education.[42] In 1831, as Thomas and other family members prepared to move to a new homestead in Coles County, Illinois, Abraham struck out on his own.[43] He made his home in New Salem, Illinois, for six years.[44] Lincoln and some friends took goods, including live hogs, by flatboat to New Orleans, Louisiana, where he first witnessed slavery.[45]

Marriage and children

Speculation persists that Lincoln's first romantic interest was Ann Rutledge, whom he met when he moved to New Salem. However, witness testimony, given decades afterward, showed a lack of any specific recollection of a romance between the two.[46] Rutledge died on August 25, 1835, most likely of typhoid fever; Lincoln took the death very hard, saying that he could not bear the idea of rain falling on Ann's grave. Lincoln sank into a serious episode of depression, and this gave rise to speculation that he had been in love with her.[47][48][49]

In the early 1830s, he met Mary Owens from Kentucky.[50] Late in 1836, Lincoln agreed to a match with Owens if she returned to New Salem. Owens arrived that November and he courted her; however, they both had second thoughts. On August 16, 1837, he wrote Owens a letter saying he would not blame her if she ended the relationship, and she never replied.[51]

In 1839, Lincoln met Mary Todd in Springfield, Illinois, and the following year they became engaged.[52] She was the daughter of Robert Smith Todd, a wealthy lawyer and businessman in Lexington, Kentucky.[53] Their wedding, which was set for January 1, 1841, was canceled because Lincoln did not appear, but they reconciled and married on November 4, 1842, in the Springfield home of Mary's sister.[54] While anxiously preparing for the nuptials, he was asked where he was going and replied, "To hell, I suppose".[55] In 1844, the couple bought a house in Springfield near his law office. Mary kept house with the help of a hired servant and a relative.[56]

Lincoln was an affectionate husband and father of four sons, though his work regularly kept him away from home. The eldest, Robert Todd Lincoln, was born in 1843, and was the only child to live to maturity. Edward Baker Lincoln (Eddie), born in 1846, died February 1, 1850, probably of tuberculosis. Lincoln's third son, "Willie" Lincoln was born on December 21, 1850, and died of a fever at the White House on February 20, 1862. The youngest, Thomas "Tad" Lincoln, was born on April 4, 1853, and survived his father, but died of heart failure at age 18 on July 16, 1871.[57][f]

Lincoln "was remarkably fond of children"[59] and the Lincolns were not considered to be strict with their own.[60] In fact, Lincoln's law partner William H. Herndon would grow irritated when Lincoln brought his children to the law office. Their father, it seemed, was often too absorbed in his work to notice his children's behavior. Herndon recounted, "I have felt many and many a time that I wanted to wring their little necks, and yet out of respect for Lincoln I kept my mouth shut. Lincoln did not note what his children were doing or had done."[61]

The deaths of their sons Eddie and Willie had profound effects on both parents. Lincoln suffered from "melancholy", a condition now thought to be clinical depression.[48] Later in life, Mary struggled with the stresses of losing her husband and sons, and in 1875 Robert committed her to an asylum.[62]

Early career and militia service

During 1831 and 1832, Lincoln worked at a general store in New Salem, Illinois. In 1832, he declared his candidacy for the Illinois House of Representatives, but interrupted his campaign to serve as a captain in the Illinois Militia during the Black Hawk War.[63] When Lincoln returned home from the Black Hawk War, he planned to become a blacksmith, but instead formed a partnership with 21-year-old William Berry, with whom he purchased a New Salem general store on credit. Because a license was required to sell customers beverages, Berry obtained bartending licenses for $7 each for Lincoln and himself, and in 1833 the Lincoln-Berry General Store became a tavern as well.[citation needed]

As licensed bartenders, Lincoln and Berry were able to sell spirits, including liquor, for 12 cents a pint. They offered a wide range of alcoholic beverages as well as food, including takeout dinners. But Berry became an alcoholic, was often too drunk to work, and Lincoln ended up running the store by himself.[64] Although the economy was booming, the business struggled and went into debt, causing Lincoln to sell his share.[citation needed]

In his first campaign speech after returning from his military service, Lincoln observed a supporter in the crowd under attack, grabbed the assailant by his "neck and the seat of his trousers", and tossed him.[40] In the campaign, Lincoln advocated for navigational improvements on the Sangamon River. He could draw crowds as a raconteur, but lacked the requisite formal education, powerful friends, and money, and lost the election.[65] Lincoln finished eighth out of 13 candidates (the top four were elected), though he received 277 of the 300 votes cast in the New Salem precinct.[66]

Lincoln served as New Salem's postmaster and later as county surveyor, but continued his voracious reading and decided to become a lawyer.[67] Rather than studying in the office of an established attorney, as was the custom, Lincoln borrowed legal texts from attorneys John Todd Stuart and Thomas Drummond, purchased books including Blackstone's Commentaries and Chitty's Pleadings, and read law on his own.[67] He later said of his legal education that "I studied with nobody."[68]

Illinois state legislature (1834–1842)

Lincoln's second state house campaign in 1834, this time as a Whig, was a success over a powerful Whig opponent.[69] Then followed his four terms in the Illinois House of Representatives for Sangamon County.[70] He championed construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, and later was a Canal Commissioner.[71] He voted to expand suffrage beyond white landowners to all white males, but adopted a "free soil" stance opposing both slavery and abolition.[72] In 1837, he declared, "[The] Institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy, but the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils."[73] He echoed Henry Clay's support for the American Colonization Society which advocated a program of abolition in conjunction with settling freed slaves in Liberia.[74]

He was admitted to the Illinois bar on September 9, 1836,[75][76] and moved to Springfield and began to practice law under John T. Stuart, Mary Todd's cousin.[77] Lincoln emerged as a formidable trial combatant during cross-examinations and closing arguments. He partnered several years with Stephen T. Logan, and in 1844, began his practice with William Herndon, "a studious young man".[78]

On January 27, 1838, Abraham Lincoln, then 28 years old, delivered his first major speech at the Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois, after the murder of newspaper editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy in Alton. Lincoln warned that no trans-Atlantic military giant could ever crush the U.S. as a nation. "It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher", said Lincoln.[79][80] Prior to that, on April 28, 1836, a black man, Francis McIntosh, was burned alive in St. Louis, Missouri. Zann Gill describes how these two murders set off a chain reaction that ultimately prompted Abraham Lincoln to run for President.[81]

U.S. House of Representatives (1847–1849)

- 30%-40% 50%-60% 60%-70% 70%-80%

- 50%-60%

True to his record, Lincoln professed to friends in 1861 to be "an old line Whig, a disciple of Henry Clay".[82] Their party favored economic modernization in banking, tariffs to fund internal improvements including railroads, and urbanization.[83]

In 1843, Lincoln sought the Whig nomination for Illinois's 7th district seat in the U.S. House of Representatives; he was defeated by John J. Hardin, though he prevailed with the party in limiting Hardin to one term. Lincoln not only pulled off his strategy of gaining the nomination in 1846, but also won the election. He was the only Whig in the Illinois delegation, but as dutiful as any participated in almost all votes and made speeches that toed the party line.[84] He was assigned to the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads and the Committee on Expenditures in the War Department.[85] Lincoln teamed with Joshua R. Giddings on a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for the owners, enforcement to capture fugitive slaves, and a popular vote on the matter. He dropped the bill when it eluded Whig support.[86][87]

Political views

On foreign and military policy, Lincoln spoke against the Mexican–American War, which he imputed President James K. Polk's desire for "military glory — that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood".[88] He supported the Wilmot Proviso, a failed proposal to ban slavery in any U.S. territory won from Mexico.[89]

Lincoln emphasized his opposition to Polk by drafting and introducing his Spot Resolutions. The war had begun with a killing of American soldiers by Mexican cavalry patrol in disputed territory, and Polk insisted that Mexican soldiers had "invaded our territory and shed the blood of our fellow-citizens on our own soil".[90] Lincoln demanded that Polk show Congress the exact spot on which blood had been shed and prove that the spot was on American soil.[91] The resolution was ignored in both Congress and the national papers, and it cost Lincoln political support in his district. One Illinois newspaper derisively nicknamed him "spotty Lincoln".[92] Lincoln later regretted some of his statements, especially his attack on presidential war-making powers.[93]

Lincoln had pledged in 1846 to serve only one term in the House. Realizing Clay was unlikely to win the presidency, he supported General Zachary Taylor for the Whig nomination in the 1848 presidential election.[94] Taylor won and Lincoln hoped in vain to be appointed Commissioner of the United States General Land Office.[95] The administration offered to appoint him secretary or governor of the Oregon Territory as consolation.[96] This distant territory was a Democratic stronghold, and acceptance of the post would have disrupted his legal and political career in Illinois, so he declined and resumed his law practice.[97]

Prairie lawyer

In his Springfield practice, Lincoln handled "every kind of business that could come before a prairie lawyer".[98] Twice a year he appeared for 10 consecutive weeks in county seats in the Midstate county courts; this continued for 16 years.[99] Lincoln handled transportation cases in the midst of the nation's western expansion, particularly river barge conflicts under the many new railroad bridges. As a riverboat man, Lincoln initially favored those interests, but ultimately represented whoever hired him.[100] He later represented a bridge company against a riverboat company in Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company, a landmark case involving a canal boat that sank after hitting a bridge.[101] In 1849 he received a patent for a flotation device for the movement of boats in shallow water. The idea was never commercialized, but it made Lincoln the only president to hold a patent.[102]

Lincoln appeared before the Illinois Supreme Court in 175 cases; he was sole counsel in 51 cases, of which 31 were decided in his favor.[103] From 1853 to 1860, one of his largest clients was the Illinois Central Railroad.[104] His legal reputation gave rise to the nickname "Honest Abe".[105]

In an 1858 criminal trial, Lincoln represented William "Duff" Armstrong, who was on trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker.[106] The case is famous for Lincoln's use of a fact established by judicial notice to challenge the credibility of an eyewitness. After an opposing witness testified to seeing the crime in the moonlight, Lincoln produced a Farmers' Almanac showing the Moon was at a low angle, drastically reducing visibility. Armstrong was acquitted.[106]

In an 1859 murder case, leading up to his presidential campaign, Lincoln elevated his profile with his defense of Simeon Quinn "Peachy" Harrison, who was a third cousin;[g] Harrison was also the grandson of Lincoln's political opponent, Rev. Peter Cartwright.[108] Harrison was charged with the murder of Greek Crafton who, as he lay dying of his wounds, confessed to Cartwright that he had provoked Harrison.[109] Lincoln angrily protested the judge's initial decision to exclude Cartwright's testimony about the confession as inadmissible hearsay. Lincoln argued that the testimony involved a dying declaration and was not subject to the hearsay rule. Instead of holding Lincoln in contempt of court as expected, the judge, a Democrat, reversed his ruling and admitted the testimony into evidence, resulting in Harrison's acquittal.[106]

Republican politics (1854–1860)

Emergence as Republican leader

The debate over the status of slavery in the territories failed to alleviate tensions between the slave-holding South and the free North, with the failure of the Compromise of 1850, a legislative package designed to address the issue.[110] In his 1852 eulogy for Clay, Lincoln highlighted the latter's support for gradual emancipation and opposition to "both extremes" on the slavery issue.[111] As the slavery debate in the Nebraska and Kansas territories became particularly acrimonious, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed popular sovereignty as a compromise; the measure would allow the electorate of each territory to decide the status of slavery. The legislation alarmed many Northerners, who sought to prevent the spread of slavery that could result, but Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act narrowly passed Congress in May 1854.[112]

Lincoln did not comment on the act until months later in his "Peoria Speech" of October 1854. Lincoln then declared his opposition to slavery, which he repeated en route to the presidency.[113] He said the Kansas Act had a "declared indifference, but as I must think, a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world...."[114] Lincoln's attacks on the Kansas–Nebraska Act marked his return to political life.[115]

Nationally the Whigs were irreparably split by the Kansas–Nebraska Act and other efforts to compromise on the slavery issue. Reflecting on the demise of his party, Lincoln wrote in 1855, "I think I am a Whig, but others say there are no Whigs, and that I am an abolitionist. ... I do no more than oppose the extension of slavery."[116] The new Republican Party was formed as a northern party dedicated to antislavery, drawing from the antislavery wing of the Whig Party and combining Free Soil, Liberty, and antislavery Democratic Party members,[117] Lincoln resisted early Republican entreaties, fearing that the new party would become a platform for extreme abolitionists.[118] Lincoln held out hope for rejuvenating the Whigs, though he lamented his party's growing closeness with the nativist Know Nothing movement.[119]

In 1854, Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature, but before the term began in January he declined to take his seat so that he would be eligible to be a candidate in the upcoming U.S. Senate election.[120][121] The year's elections showed the strong opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and in the aftermath Lincoln sought election to the U.S. Senate.[115] At that time, senators were elected by state legislatures.[122] After leading in the first six rounds of voting, he was unable to obtain a majority. Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull. Trumbull was an antislavery Democrat and had received few votes in the earlier ballots; his supporters, also antislavery Democrats, had vowed not to support any Whig. Lincoln's decision to withdraw enabled his Whig supporters and Trumbull's antislavery Democrats to combine and defeat the mainstream Democratic candidate, Joel Aldrich Matteson.[123]

1856 campaign

Violent political confrontations in Kansas continued, and opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act remained strong throughout the North. As the 1856 elections approached, Lincoln joined the Republicans and attended the Bloomington Convention, which formally established the Illinois Republican Party. The convention platform endorsed Congress's right to regulate slavery in the territories and backed the admission of Kansas as a free state. Lincoln gave the final speech of the convention supporting the party platform and called for the preservation of the Union.[124] At the June 1856 Republican National Convention, though Lincoln received support to run as vice president, John C. Frémont and William Dayton were on the ticket, which Lincoln supported throughout Illinois. The Democrats nominated former Secretary of State James Buchanan and the Know-Nothings nominated former Whig President Millard Fillmore.[125] Buchanan prevailed, while Republican William Henry Bissell won election as Governor of Illinois, and Lincoln became a leading Republican in Illinois.[126][h]

Dred Scott v. Sandford

Dred Scott was a slave whose master took him from a slave state to a territory that was free as a result of the Missouri Compromise. After Scott was returned to the slave state, he petitioned a federal court for his freedom. His petition was denied in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857).[i] In his opinion, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney wrote that black people were not citizens and derived no rights from the Constitution, and that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional for infringing upon slave owners' "property" rights. While many Democrats hoped that Dred Scott would end the dispute over slavery in the territories, the decision sparked further outrage in the North.[129] Lincoln denounced it as the product of a conspiracy of Democrats to support the Slave Power.[130] He argued the decision was at variance with the Declaration of Independence; he said that while the founding fathers did not believe all men equal in every respect, they believed all men were equal "in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness".[131]

Lincoln–Douglas debates and Cooper Union speech

In 1858, Douglas was up for re-election in the U.S. Senate, and Lincoln hoped to defeat him. Many in the party felt that a former Whig should be nominated in 1858, and Lincoln's 1856 campaigning and support of Trumbull had earned him a favor.[132] Some eastern Republicans supported Douglas for his opposition to the Lecompton Constitution and admission of Kansas as a slave state.[133] Many Illinois Republicans resented this eastern interference. For the first time, Illinois Republicans held a convention to agree upon a Senate candidate, and Lincoln won the nomination with little opposition.[134]

Lincoln accepted the nomination with great enthusiasm and zeal. After his nomination he delivered his House Divided Speech, with the biblical reference Mark 3:25, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other."[135] The speech created a stark image of the danger of disunion.[136] The stage was then set for the election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas.[137] When informed of Lincoln's nomination, Douglas stated, "[Lincoln] is the strong man of the party ... and if I beat him, my victory will be hardly won."[138]

The Senate campaign featured seven debates between Lincoln and Douglas. These were the most famous political debates in American history; they had an atmosphere akin to a prizefight and drew crowds in the thousands.[139] The principals stood in stark contrast both physically and politically. Lincoln warned that the Slave Power was threatening the values of republicanism, and he accused Douglas of distorting the Founding Fathers' premise that all men are created equal. In his Freeport Doctrine, Douglas argued that, despite the Dred Scott decision, which he claimed to support,[140] local settlers, under the doctrine of popular sovereignty, should be free to choose whether to allow slavery within their territory, and he accused Lincoln of having joined the abolitionists.[141] Lincoln's argument assumed a moral tone, as he claimed that Douglas represented a conspiracy to promote slavery. Douglas's argument was more legal in nature, claiming that Lincoln was defying the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court as exercised in the Dred Scott decision.[142]

Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats, and the legislature re-elected Douglas. However, Lincoln's articulation of the issues had given him a national political presence.[143] In May 1859, Lincoln purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, a German-language newspaper that was consistently supportive; most of the state's 130,000 German Americans voted for Democrats, but the German-language paper mobilized Republican support.[144] In the aftermath of the 1858 election, newspapers frequently mentioned Lincoln as a potential Republican presidential candidate, rivaled by William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Simon Cameron. While Lincoln was popular in the Midwest, he lacked support in the Northeast and was unsure whether to seek the office.[145] In January 1860, Lincoln told a group of political allies that he would accept the presidential nomination if offered and, in the following months, several local papers endorsed his candidacy.[146]

Over the coming months Lincoln was tireless, making nearly fifty speeches along the campaign trail. By the quality and simplicity of his rhetoric, he quickly became the champion of the Republican party. However, despite his overwhelming support in the Midwestern United States, he was less appreciated in the east. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, at that time wrote up an unflattering account of Lincoln's compromising position on slavery and his reluctance to challenge the court's Dred Scott ruling, which was promptly used against him by his political rivals.[147][148]

On February 27, 1860, powerful New York Republicans invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union, in which he argued that the Founding Fathers of the United States had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery. He insisted that morality required opposition to slavery and rejected any "groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong".[149] Many in the audience thought he appeared awkward and even ugly.[150] But Lincoln demonstrated intellectual leadership, which brought him into contention. Journalist Noah Brooks reported, "No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience".[151]

Historian David Herbert Donald described the speech as "a superb political move for an unannounced presidential aspirant. Appearing in Seward's home state, sponsored by a group largely loyal to Chase, Lincoln shrewdly made no reference to either of these Republican rivals for the nomination."[152] In response to an inquiry about his ambitions, Lincoln said, "The taste is in my mouth a little".[153]

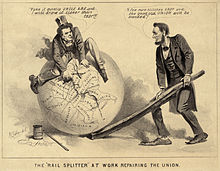

1860 presidential election

On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur.[154] Lincoln's followers organized a campaign team led by David Davis, Norman Judd, Leonard Swett, and Jesse DuBois, and Lincoln received his first endorsement.[155] Exploiting his embellished frontier legend (clearing land and splitting fence rails), Lincoln's supporters adopted the label of "The Rail Candidate".[156] In 1860, Lincoln described himself: "I am in height, six feet, four inches, nearly; lean in flesh, weighing, on an average, one hundred and eighty pounds; dark complexion, with coarse black hair, and gray eyes."[157] Michael Martinez wrote about the effective imaging of Lincoln by his campaign. At times he was presented as the plain-talking "Rail Splitter" and at other times he was "Honest Abe", unpolished but trustworthy.[158]

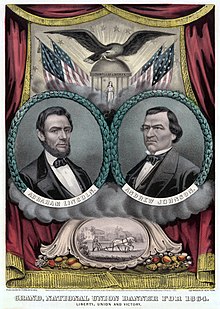

On May 18 at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Lincoln won the nomination on the third ballot, beating candidates such as Seward and Chase. A former Democrat, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, was nominated for vice president to balance the ticket. Lincoln's success depended on his campaign team, his reputation as a moderate on the slavery issue, and his strong support for internal improvements and the tariff.[159] Pennsylvania put him over the top, led by the state's iron interests who were reassured by his tariff support.[160] Lincoln's managers had focused on this delegation while honoring Lincoln's dictate to "Make no contracts that will bind me".[161]

As the Slave Power tightened its grip on the national government, most Republicans agreed with Lincoln that the North was the aggrieved party. Throughout the 1850s, Lincoln had doubted the prospects of civil war, and his supporters rejected claims that his election would incite secession.[162] When Douglas was selected as the candidate of the Northern Democrats, delegates from eleven slave states walked out of the Democratic convention; they opposed Douglas's position on popular sovereignty, and selected incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge as their candidate.[163] A group of former Whigs and Know Nothings formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee. Lincoln and Douglas competed for votes in the North, while Bell and Breckinridge primarily found support in the South.[132]

Before the Republican convention, the Lincoln campaign began cultivating a nationwide youth organization, the Wide Awakes, which it used to generate popular support throughout the country to spearhead voter registration drives, thinking that new voters and young voters tended to embrace new parties.[164] People of the Northern states knew the Southern states would vote against Lincoln and rallied supporters for Lincoln.[165]

As Douglas and the other candidates campaigned, Lincoln gave no speeches, relying on the enthusiasm of the Republican Party. The party did the leg work that produced majorities across the North and produced an abundance of campaign posters, leaflets, and newspaper editorials. Republican speakers focused first on the party platform, and second on Lincoln's life story, emphasizing his childhood poverty. The goal was to demonstrate the power of "free labor", which allowed a common farm boy to work his way to the top by his own efforts.[166] The Republican Party's production of campaign literature dwarfed the combined opposition; a Chicago Tribune writer produced a pamphlet that detailed Lincoln's life and sold 100,000–200,000 copies.[167] Though he did not give public appearances, many sought to visit him and write him. In the runup to the election, he took an office in the Illinois state capitol to deal with the influx of attention. He also hired John George Nicolay as his personal secretary, who would remain in that role during the presidency.[168]

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected the 16th president. He was the first Republican president and his victory was entirely due to his support in the North and West. No ballots were cast for him in 10 of the 15 Southern slave states, and he won only two of 996 counties in all the Southern states, an omen of the impending Civil War.[169][170] Lincoln received 1,866,452 votes, or 39.8% of the total in a four-way race, carrying the free Northern states, as well as California and Oregon.[171] His victory in the Electoral College was decisive: Lincoln had 180 votes to 123 for his opponents.[172]

Presidency (1861–1865)

Secession and inauguration

The South was outraged by Lincoln's election, and in response secessionists implemented plans to leave the Union before he took office in March 1861.[174] On December 20, 1860, South Carolina took the lead by adopting an ordinance of secession; by February 1, 1861, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed.[175] Six of these states declared themselves to be a sovereign nation, the Confederate States of America, and adopted a constitution.[176] Most of the the upper South and border states (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas) initially rejected the secessionist appeal act for the time being, although four of these states (Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina) would inevitably secede once war broke out.[177] President Buchanan and President-elect Lincoln refused to recognize the Confederacy, declaring secession illegal.[178] The Confederacy selected Jefferson Davis as its provisional president on February 9, 1861.[179]

Attempts at compromise followed but Lincoln and the Republicans rejected the proposed Crittenden Compromise as contrary to the Party's platform of free-soil in the territories.[180] Lincoln said, "I will suffer death before I consent ... to any concession or compromise which looks like buying the privilege to take possession of this government to which we have a constitutional right".[181]

Lincoln supported the Corwin Amendment to the Constitution, which passed Congress and was awaiting ratification by the states when Lincoln took office. That doomed amendment would have protected slavery in states where it already existed.[182] On March 4, 1861, in his first inaugural address, Lincoln said that, because he holds "such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable".[183] A few weeks before the war, Lincoln sent a letter to every governor informing them Congress had passed a joint resolution to amend the Constitution.[184]

On February 11, 1861, Lincoln gave a particularly emotional farewell address upon leaving Springfield; he would never again return to Springfield alive.[185][186] Lincoln traveled east in a special train. Due to secessionist plots, a then-unprecedented attention to security was given to him and his train. En route to his inauguration, Lincoln addressed crowds and legislatures across the North.[187] The president-elect evaded suspected assassins in Baltimore. He traveled in disguise, wearing a soft felt hat instead of his customary stovepipe hat and draping an overcoat over his shoulders while hunching slightly to conceal his height. His friend Congressman Elihu B. Washburne recognized him on the platform upon arrival and loudly called out to him.[188] On February 23, 1861, he arrived in Washington, D.C., which was placed under substantial military guard.[189] Lincoln directed his inaugural address to the South, proclaiming once again that he had no inclination to abolish slavery in the Southern states:

Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States, that by the accession of a Republican Administration, their property, and their peace, and personal security, are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed, and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that "I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so."

Lincoln cited his plans for banning the expansion of slavery as the key source of conflict between North and South, stating "One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute." The president ended his address with an appeal to the people of the South: "We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.... The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."[192] The failure of the Peace Conference of 1861 signaled that legislative compromise was impossible. By March 1861, no leaders of the insurrection had proposed rejoining the Union on any terms. Meanwhile, Lincoln and the Republican leadership agreed that the dismantling of the Union could not be tolerated.[193] In his second inaugural address, Lincoln looked back on the situation at the time and said: "Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the Nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came."

Civil War

Major Robert Anderson, commander of the Union's Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, sent a request for provisions to Washington, and Lincoln's order to meet that request was seen by the secessionists as an act of war. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on Union troops at Fort Sumter and began the fight. Historian Allan Nevins argued that the newly inaugurated Lincoln made three miscalculations: underestimating the gravity of the crisis, exaggerating the strength of Unionist sentiment in the South, and overlooking Southern Unionist opposition to an invasion.[194]

William Tecumseh Sherman talked to Lincoln during inauguration week and was "sadly disappointed" at his failure to realize that "the country was sleeping on a volcano" and that the South was preparing for war.[195] Donald concludes, "His repeated efforts to avoid collision in the months between inauguration and the firing on Fort Sumter showed he adhered to his vow not to be the first to shed fraternal blood. But he had also vowed not to surrender the forts.... The only resolution of these contradictory positions was for the Confederates to fire the first shot". They did just that.[196]

On April 15, Lincoln called on the states to send a total of 75,000 volunteer troops to recapture forts, protect Washington, and "preserve the Union", which, in his view, remained intact despite the seceding states. This call forced states to choose sides. Virginia seceded and was rewarded with the designation of Richmond as the Confederate capital, despite its exposure to Union lines. North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas followed over the following two months. Secession sentiment was strong in Missouri and Maryland, but did not prevail; Kentucky remained neutral.[197] The Fort Sumter attack rallied Americans north of the Mason-Dixon line to defend the nation.

As states sent Union regiments south, on April 19 Baltimore mobs in control of the rail links attacked Union troops who were changing trains. Local leaders' groups later burned critical rail bridges to the capital and the Army responded by arresting local Maryland officials. Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus in an effort to protect the troops trying to reach Washington.[198] John Merryman, one Maryland official hindering the U.S. troop movements, petitioned Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney to issue a writ of habeas corpus. In June, in Ex parte Merryman, Taney, not ruling on behalf of the Supreme Court,[199] issued the writ, believing that Article I, section 9 of the Constitution authorized only Congress and not the president to suspend it. But Lincoln invoked nonacquiescence and persisted with the policy of suspension in select areas.[200][201]

Union military strategy

Lincoln took executive control of the war and shaped the Union military strategy. He responded to the unprecedented political and military crisis as commander-in-chief by exercising unprecedented authority. He expanded his war powers, imposed a blockade on Confederate ports, disbursed funds before appropriation by Congress, suspended habeas corpus, and arrested and imprisoned thousands of suspected Confederate sympathizers. Lincoln gained the support of Congress and the northern public for these actions. Lincoln also had to reinforce Union sympathies in the border slave states and keep the war from becoming an international conflict.[202]

It was clear from the outset that bipartisan support was essential to success, and that any compromise alienated factions on both sides of the aisle, such as the appointment of Republicans and Democrats to command positions. Copperheads criticized Lincoln for refusing to compromise on slavery. The Radical Republicans criticized him for moving too slowly in abolishing slavery.[203] On August 6, 1861, Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act of 1861, which authorized judicial proceedings to confiscate and free slaves who were used to support the Confederates. The law had little practical effect, but it signaled political support for abolishing slavery.[204]

In August 1861, General John C. Frémont, the 1856 Republican presidential nominee, without consulting Washington, issued a martial edict freeing slaves of the rebels. Lincoln canceled the proclamation as violating the Confiscation Act of 1861 and beyond Frémont's authority to issue.[205] As a result, Union enlistments from Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri increased by over 40,000.[206]

Internationally, Lincoln wanted to forestall foreign military aid to the Confederacy.[207] He relied on his combative Secretary of State William Seward while working closely with Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Charles Sumner.[208] In the 1861 Trent Affair, which threatened war with Great Britain, the U.S. Navy illegally intercepted a British mail ship, the Trent, on the high seas and seized two Confederate envoys; Britain protested vehemently while the U.S. cheered. Lincoln ended the crisis by releasing the two diplomats. Biographer James G. Randall dissected Lincoln's successful techniques:[209]

his restraint, his avoidance of any outward expression of truculence, his early softening of State Department's attitude toward Britain, his deference toward Seward and Sumner, his withholding of his paper prepared for the occasion, his readiness to arbitrate, his golden silence in addressing Congress, his shrewdness in recognizing that war must be averted, and his clear perception that a point could be clinched for America's true position at the same time that full satisfaction was given to a friendly country.

Lincoln painstakingly monitored the telegraph reports coming into the War Department. He tracked all phases of the effort, consulting with governors and selecting generals based on their success, their state, and their party. In January 1862, after complaints of inefficiency and profiteering in the War Department, Lincoln replaced War Secretary Simon Cameron with Edwin Stanton. Stanton centralized the War Department's activities, auditing and canceling contracts, saving the federal government $17,000,000.[210] Stanton was a staunch Unionist, pro-business, conservative Democrat who gravitated toward the Radical Republican faction. He worked more often and more closely with Lincoln than did any other senior official. "Stanton and Lincoln virtually conducted the war together", say Thomas and Hyman.[211]

Lincoln's war strategy had two priorities: ensuring that Washington was well-defended and conducting an aggressive war effort for a prompt, decisive victory.[j] Twice a week, Lincoln met with his cabinet in the afternoon. Occasionally Mary prevailed on him to take a carriage ride, concerned that he was working too hard.[213] For his edification Lincoln relied upon a book by his chief of staff General Henry Halleck entitled Elements of Military Art and Science; Halleck was a disciple of the European strategist Antoine-Henri Jomini. Lincoln began to appreciate the critical need to control strategic points, such as the Mississippi River.[214] Lincoln saw the importance of Vicksburg and understood the necessity of defeating the enemy's army, rather than merely capturing territory.[215]

In directing the Union's war strategy, Lincoln valued the advice of Gen. Winfield Scott, even after his retirement as Commanding General of the United States Army. On June 23–24, 1862, Lincoln made an unannounced visit to West Point, where he spent five hours consulting with Scott regarding the handling of the Civil War and the staffing of the War Department.[216][217]

General McClellan

After the Union rout at Bull Run and Winfield Scott's retirement, Lincoln appointed Major General George B. McClellan general-in-chief.[218] McClellan then took months to plan his Virginia Peninsula Campaign. McClellan's slow progress frustrated Lincoln, as did his position that no troops were needed to defend Washington. McClellan, in turn, blamed the failure of the campaign on Lincoln's reservation of troops for the capital.[219]

In 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan for the general's continued inaction. He elevated Henry Halleck in July and appointed John Pope as head of the new Army of Virginia.[220] Pope satisfied Lincoln's desire to advance on Richmond from the north, thereby protecting Washington from counterattack.[221] But in the summer of 1862 Pope was soundly defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run, forcing the Army of the Potomac back to defend Washington.[222]

Despite his dissatisfaction with McClellan's failure to reinforce Pope, Lincoln restored him to command of all forces around Washington.[223] Two days after McClellan's return to command, General Robert E. Lee's forces crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, leading to the Battle of Antietam.[224] That battle, a Union victory, was among the bloodiest in American history; it facilitated Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in January.[225]

McClellan then resisted the president's demand that he pursue Lee's withdrawing army, while General Don Carlos Buell likewise refused orders to move the Army of the Ohio against rebel forces in eastern Tennessee. Lincoln replaced Buell with William Rosecrans; and after the 1862 midterm elections he replaced McClellan with Ambrose Burnside. The appointments were both politically neutral and adroit on Lincoln's part.[226]

Against presidential advice Burnside launched an offensive across the Rappahannock River and was defeated by Lee at Fredericksburg in December. Desertions during 1863 came in the thousands and only increased after Fredericksburg, so Lincoln replaced Burnside with Joseph Hooker.[227]

In the 1862 midterm elections, the Republicans suffered severe losses due to rising inflation, high taxes, rumors of corruption, suspension of habeas corpus, military draft law, and fears that freed slaves would come North and undermine the labor market. The Emancipation Proclamation gained votes for Republicans in rural New England and the upper Midwest, but cost votes in the Irish and German strongholds and in the lower Midwest, where many Southerners had lived for generations.[228]

In the spring of 1863, Lincoln was sufficiently optimistic about upcoming military campaigns to think the end of the war could be near; the plans included attacks by Hooker on Lee north of Richmond, Rosecrans on Chattanooga, Grant on Vicksburg, and a naval assault on Charleston.[229]

Hooker was routed by Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May, then resigned and was replaced by George Meade.[230] Meade followed Lee north into Pennsylvania and beat him in the Gettysburg Campaign, but then failed to follow up despite Lincoln's demands. At the same time, Grant captured Vicksburg and gained control of the Mississippi River, splitting the far western rebel states.[231]

Emancipation Proclamation

The federal government's power to end slavery was limited by the Constitution, which before 1865, was understood to reserve the issue to the individual states. Lincoln believed that slavery would be rendered obsolete if its expansion into new territories were prevented, because these territories would be admitted to the Union as free states, and free states would come to outnumber slave states. He sought to persuade the states to agree to compensation for emancipating their slaves.[232] Lincoln rejected Major General John C. Frémont's August 1861 emancipation attempt, as well as one by Major General David Hunter in May 1862, on the grounds that it was not within their power and might upset loyal border states enough for them to secede.[233]

In June 1862, Congress passed an act banning slavery on all federal territory, which Lincoln signed. In July, the Confiscation Act of 1862 was enacted, providing court procedures to free the slaves of those convicted of aiding the rebellion; Lincoln approved the bill despite his belief that it was unconstitutional. He felt such action could be taken only within the war powers of the commander-in-chief, which he planned to exercise. On July 22, 1862, Lincoln reviewed a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation with his cabinet.[234]

Peace Democrats (Copperheads) argued that emancipation was a stumbling block to peace and reunification, but Republican editor Horace Greeley of the New-York Tribune, in his public letter, "The Prayer of Twenty Millions", implored Lincoln to embrace emancipation.[235][236] In a public letter of August 22, 1862, Lincoln replied to Greeley, writing that while he personally wished all men could be free, his first obligation as president was to preserve the Union:[237]

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union ... [¶] I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.[238]

When Lincoln published his reply to Greeley, he had already decided to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and therefore had already chosen the third option he mentioned in his letter to Greeley: to free some of the slaves, namely those in the states in rebellion. Some scholars, therefore, believe that his reply to Greeley was disingenuous and was intended to reassure white people who would have opposed a war for emancipation that emancipation was merely a means to preserve the Union.[239] On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation,[240] which announced that, in states still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, the slaves would be freed. He spent the next 100 days, between September 22 and January 1, preparing the army and the nation for emancipation, while Democrats rallied their voters by warning of the threat that freed slaves posed to northern whites.[241] At the same time, during those 100 days, Lincoln made efforts to end the war with slavery intact, suggesting that he still took seriously the first option he mentioned in his letter to Greeley: saving the Union without freeing any slave.[242] But, on January 1, 1863, keeping his word, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation,[243] freeing the slaves in 10 states not then under Union control,[244] with exemptions specified for areas under such control.[245] Lincoln's comment on signing the Proclamation was: "I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper."[246]

With the abolition of slavery in the rebel states now a military objective, Union armies advancing south "enable[d] thousands of slaves to escape to freedom".[247] The Emancipation Proclamation having stated that freedmen would be "received into the armed service of the United States," enlisting these freedmen became official policy. By the spring of 1863, Lincoln was ready to recruit black troops in more than token numbers. In a letter to Tennessee military governor Andrew Johnson encouraging him to lead the way in raising black troops, Lincoln wrote, "The bare sight of fifty thousand armed, and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once".[248] By the end of 1863, at Lincoln's direction, General Lorenzo Thomas "had enrolled twenty regiments of African Americans" from the Mississippi Valley.[248]

Gettysburg Address (1863)

Lincoln spoke at the dedication of the Gettysburg battlefield cemetery on November 19, 1863.[251] In 272 words, and three minutes, Lincoln asserted that the nation was born not in 1789, but in 1776, "conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal". He defined the war as dedicated to the principles of liberty and equality for all. He declared that the deaths of so many brave soldiers would not be in vain, that the future of democracy would be assured, and that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth".[252]

Defying his prediction that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here", the Address became the most quoted speech in American history.[253]

Promoting General Grant

General Ulysses Grant's victories at the Battle of Shiloh and in the Vicksburg campaign impressed Lincoln. Responding to criticism of Grant after Shiloh, Lincoln had said, "I can't spare this man. He fights."[254] With Grant in command, Lincoln felt the Union Army could advance in multiple theaters, while also including black troops. Meade's failure to capture Lee's army after Gettysburg and the continued passivity of the Army of the Potomac persuaded Lincoln to promote Grant to supreme commander. Grant then assumed command of Meade's army.[255]

Lincoln was concerned that Grant might be considering a presidential candidacy in 1864. He arranged for an intermediary to inquire into Grant's political intentions, and once assured that he had none, Lincoln promoted Grant to the newly revived rank of Lieutenant General, a rank which had been unoccupied since George Washington.[256] Authorization for such a promotion "with the advice and consent of the Senate" was provided by a new bill which Lincoln signed the same day he submitted Grant's name to the Senate. His nomination was confirmed by the Senate on March 2, 1864.[257]

Grant in 1864 waged the bloody Overland Campaign, which exacted heavy losses on both sides.[258] When Lincoln asked what Grant's plans were, the persistent general replied, "I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer."[259] Grant's army moved steadily south. Lincoln traveled to Grant's headquarters at City Point, Virginia, to confer with Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman.[260] Lincoln reacted to Union losses by mobilizing support throughout the North.[261] Lincoln authorized Grant to target infrastructure—plantations, railroads, and bridges—hoping to weaken the South's morale and fighting ability. He emphasized defeat of the Confederate armies over destruction (which was considerable) for its own sake.[262] Lincoln's engagement became distinctly personal on one occasion in 1864 when Confederate general Jubal Early raided Washington, D.C. Legend has it that while Lincoln watched from an exposed position, Union Captain (and future Supreme Court Justice) Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. shouted at him, "Get down, you damn fool, before you get shot!" But this story is commonly regarded as apocryphal.[263][264][265][266]

As Grant continued to weaken Lee's forces, efforts to discuss peace began. Confederate Vice President Stephens led a group meeting with Lincoln, Seward, and others at Hampton Roads. Lincoln refused to negotiate with the Confederacy as a coequal; his objective to end the fighting was not realized.[267] On April 1, 1865, Grant nearly encircled Petersburg in a siege. The Confederate government evacuated Richmond and Lincoln visited the conquered capital. On April 9, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, officially ending the war.[268]

Reelection

Lincoln ran for reelection in 1864, while uniting the main Republican factions along with War Democrats Edwin M. Stanton and Andrew Johnson. Lincoln used conversation and his patronage powers—greatly expanded from peacetime—to build support and fend off the Radicals' efforts to replace him.[269] At its convention, the Republican Party selected Johnson as his running mate. To broaden his coalition to include War Democrats as well as Republicans, Lincoln ran under the label of the new Union Party.[270]

Grant's bloody stalemates damaged Lincoln's re-election prospects, and many Republicans feared defeat. Lincoln confidentially pledged in writing that if he should lose the election, he would still defeat the Confederacy before turning over the White House;[271] Lincoln did not show the pledge to his cabinet, but asked them to sign the sealed envelope. The pledge read as follows:

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterward.[272]

The Democratic platform followed the "Peace wing" of the party and called the war a "failure"; but their candidate, McClellan, supported the war and repudiated the platform. Meanwhile, Lincoln emboldened Grant with more troops and Republican party support. Sherman's capture of Atlanta in September and David Farragut's capture of Mobile ended defeatism.[273] The Democratic Party was deeply split, with some leaders and most soldiers openly for Lincoln. The National Union Party was united by Lincoln's support for emancipation. State Republican parties stressed the perfidy of the Copperheads.[274] On November 8, Lincoln carried all but three states, including 78 percent of Union soldiers.[275]

On March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. In it, he deemed the war casualties to be God's will. Historian Mark Noll places the speech "among the small handful of semi-sacred texts by which Americans conceive their place in the world;" it is inscribed in the Lincoln Memorial.[276] Lincoln said:

Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, "the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether". With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.[277]

Among those present for this speech was actor John Wilkes Booth, who, on April 14, 1865, just over a month after Lincoln’s second inauguration, assassinated him.

Reconstruction

Reconstruction preceded the war's end, as Lincoln and his associates considered the reintegration of the nation, and the fates of Confederate leaders and freed slaves. When a general asked Lincoln how the defeated Confederates were to be treated, Lincoln replied, "Let 'em up easy."[278] Lincoln was determined to find meaning in the war in its aftermath, and did not want to continue to outcast the southern states. His main goal was to keep the union together, so he proceeded by focusing not on whom to blame, but on how to rebuild the nation as one.[279] Lincoln led the moderates in Reconstruction policy and was opposed by the Radicals, under Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, Sen. Charles Sumner and Sen. Benjamin Wade, who otherwise remained Lincoln's allies. Determined to reunite the nation and not alienate the South, Lincoln urged that speedy elections under generous terms be held. His Amnesty Proclamation of December 8, 1863, offered pardons to those who had not held a Confederate civil office and had not mistreated Union prisoners, if they were willing to sign an oath of allegiance.[280]

As Southern states fell, they needed leaders while their administrations were restored. In Tennessee and Arkansas, Lincoln respectively appointed Johnson and Frederick Steele as military governors. In Louisiana, Lincoln ordered General Nathaniel P. Banks to promote a plan that would reestablish statehood when 10 percent of the voters agreed, and only if the reconstructed states abolished slavery. Democratic opponents accused Lincoln of using the military to ensure his and the Republicans' political aspirations. The Radicals denounced his policy as too lenient, and passed their own plan, the 1864 Wade–Davis Bill, which Lincoln vetoed. The Radicals retaliated by refusing to seat elected representatives from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee.[281]

Lincoln's appointments were designed to harness both moderates and Radicals. To fill Chief Justice Taney's seat on the Supreme Court, he named the Radicals' choice, Salmon P. Chase, whom Lincoln believed would uphold his emancipation and paper money policies.[282]

After implementing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln increased pressure on Congress to outlaw slavery throughout the nation with a constitutional amendment. He declared that such an amendment would "clinch the whole subject" and by December 1863 an amendment was brought to Congress.[283] The Senate passed it on April 8, 1864, but the first vote in the House of Representatives fell short of the required two-thirds majority. Passage became part of Lincoln's reelection platform, and after his successful reelection, the second attempt in the House passed on January 31, 1865.[284] With ratification, it became the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 6, 1865.[285]

Lincoln believed the federal government had limited responsibility to the millions of freedmen. He signed Senator Charles Sumner's Freedmen's Bureau bill that set up a temporary federal agency designed to meet the immediate needs of former slaves. The law opened land for a lease of three years with the ability to purchase title for the freedmen. Lincoln announced a Reconstruction plan that involved short-term military control, pending readmission under the control of southern Unionists.[286]

Historians agree that it is impossible to predict how Reconstruction would have proceeded had Lincoln lived. Biographers James G. Randall and Richard Current, according to David Lincove, argue that:[287]

It is likely that had he lived, Lincoln would have followed a policy similar to Johnson's, that he would have clashed with congressional Radicals, that he would have produced a better result for the freedmen than occurred, and that his political skills would have helped him avoid Johnson's mistakes.

Eric Foner argues that:[288]

Unlike Sumner and other Radicals, Lincoln did not see Reconstruction as an opportunity for a sweeping political and social revolution beyond emancipation. He had long made clear his opposition to the confiscation and redistribution of land. He believed, as most Republicans did in April 1865, that voting requirements should be determined by the states. He assumed that political control in the South would pass to white Unionists, reluctant secessionists, and forward-looking former Confederates. But time and again during the war, Lincoln, after initial opposition, had come to embrace positions first advanced by abolitionists and Radical Republicans. ... Lincoln undoubtedly would have listened carefully to the outcry for further protection for the former slaves. ... It is entirely plausible to imagine Lincoln and Congress agreeing on a Reconstruction policy that encompassed federal protection for basic civil rights plus limited black suffrage, along the lines Lincoln proposed just before his death.

Native Americans

Lincoln's relationship with Native Americans started before he was born, with their killing of his grandfather in front of his sons, including Lincoln's father Thomas.[289] Lincoln himself served as a captain in the state militia during the Black Hawk War but saw no combat.[290] Lincoln used appointments to the Indian Bureau as a reward to supporters from Minnesota and Wisconsin. While in office his administration faced difficulties guarding Western settlers, railroads, and telegraphs, from Indian attacks.[291]

On August 17, 1862, the Dakota War broke out in Minnesota. Hundreds of settlers were killed, 30,000 were displaced from their homes, and Washington was deeply alarmed.[292] Some feared incorrectly that it might represent a Confederate conspiracy to start a war on the Northwestern frontier.[293] Lincoln ordered thousands of Confederate prisoners of war sent by railroad to put down the uprising.[294] When the Confederates protested forcing Confederate prisoners to fight Indians, Lincoln revoked the policy and none arrived in Minnesota. Lincoln sent General John Pope as commander of the new Department of the Northwest two weeks into the hostilities.[295][296] Before he arrived, the Fond Du Lac band of Chippewa sent Lincoln a letter asking to go to war for the United States against the Sioux, so Lincoln could send Minnesota's troops to fight the South.[297][298] Shortly after, a Mille Lacs Band Chief offered the same at St. Cloud, Minnesota.[299][300] In it the Chippewa specified they wanted to use the indigenous rules of warfare.[301] That meant there would be no prisoners of war, no surrender, no peace agreement.[302] Lincoln did not accept the Chippewa offer, as he could not control the Chippewa, and women and children were considered legitimate casualties in native American warfare.[303]

Serving under Gen. Pope was Minnesota Congressman Henry H. Sibley. Minnesota's Governor had made Sibley a Colonel United States Volunteers to command the U.S. force tasked with fighting the war and that eventually defeated Little Crow's forces at the Battle of Wood Lake.[296] The day the Mdewakanton force surrendered at Camp Release, a Chippewa war council met at Minnesota's capitol with another Chippewa offer to Lincoln, to fight the Sioux.[304][additional citation(s) needed] Sibley ordered a military commission to review the actions of the captured, to try those that had committed war crimes. The legitimacy of military commissions trying opposing combatants had been established during the Mexican War.[305] Sibley thought he had 16-20 of the men he wanted for trial, while Gen. Pope ordered all detained be tried. 303 were given death sentences that were subject to Presidential review. Lincoln ordered Pope send all trial transcripts to Washington, where Lincoln and two of his staff examined them. Lincoln realized the trials could be divided into two groups: combat between combatants and combat against civilians.[citation needed] The groups could be identified by their transcripts, the first group all had three pages in length while the second group had more, some up to twelve pages.[citation needed] He placed 263 cases into the first group and commuted their sentences. In the second group were forty cases. One he commuted for becoming a state's witness. Sibley dismissed another when proof surfaced exonerating the defendant. The remaining 38 were executed in the largest mass hanging in U.S. history.[citation needed] Questions arose concerning three executions that have not been answered.[306] Less than 4 months afterwards, Lincoln issued the Lieber Code, which governed wartime conduct of the Union Army, by defining command responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Congressman Alexander Ramsey told Lincoln in 1864, he would have gotten more re-election support in Minnesota had he executed all 303 of the Mdewakanton. Lincoln responded, "I could not afford to hang men for votes."[307] The men whose sentences he commuted were sent to a military prison at Davenport, Iowa. Some he released due to the efforts of Bishop Henry Whipple.

Whig theory of a presidency

Lincoln adhered to the Whig theory of a presidency focused on executing laws while deferring to Congress' responsibility for legislating. Under this philosophy, Lincoln vetoed only four bills during his presidency, including the Wade-Davis Bill with its harsh Reconstruction program.[308] The 1862 Homestead Act made millions of acres of Western government-held land available for purchase at low cost. The 1862 Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act provided government grants for agricultural colleges in each state. The Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864 granted federal support for the construction of the United States' first transcontinental railroad, which was completed in 1869.[309] The passage of the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railway Acts was enabled by the absence of Southern congressmen and senators who had opposed the measures in the 1850s.[310]

| The Lincoln cabinet[311] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Abraham Lincoln | 1861–1865 |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin | 1861–1865 |

| Andrew Johnson | 1865 | |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Salmon P. Chase | 1861–1864 |

| William P. Fessenden | 1864–1865 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron | 1861–1862 |

| Edwin M. Stanton | 1862–1865 | |

| Attorney General | Edward Bates | 1861–1864 |

| James Speed | 1864–1865 | |

| Postmaster General | Montgomery Blair | 1861–1864 |

| William Dennison Jr. | 1864–1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Caleb Blood Smith | 1861–1862 |

| John Palmer Usher | 1863–1865 | |

In the selection and use of his cabinet Lincoln employed the strengths of his opponents in a manner that emboldened his presidency. Lincoln commented on his thought process, "We need the strongest men of the party in the Cabinet. We needed to hold our own people together. I had looked the party over and concluded that these were the very strongest men. Then I had no right to deprive the country of their services."[312] Goodwin described the group in her biography as a Team of Rivals.[313]

There were two measures passed to raise revenues for the federal government: tariffs (a policy with long precedent), and a federal income tax. In 1861, Lincoln signed the second and third Morrill Tariffs, following the first enacted by Buchanan. He also signed the Revenue Act of 1861, creating the first U.S. income tax—a flat tax of 3 percent on incomes above $800 (equivalent to $27,129 in 2023[314]).[315] The Revenue Act of 1862 adopted rates that increased with income.[316]

The Lincoln Administration presided over the expansion of the federal government's economic influence in other areas. The National Banking Act created the system of national banks. The U.S. issued paper currency for the first time, known as greenbacks—printed in green on the reverse side.[317] In 1862, Congress created the Department of Agriculture.[315]

In response to rumors of a renewed draft, the editors of the New York World and the Journal of Commerce published a false draft proclamation that created an opportunity for the editors and others to corner the gold market. Lincoln attacked the media for such behavior, and ordered a military seizure of the two papers which lasted for two days.[318]

Lincoln is largely responsible for the Thanksgiving holiday.[319] Thanksgiving had become a regional holiday in New England in the 17th century. It had been sporadically proclaimed by the federal government on irregular dates. The prior proclamation had been during James Madison's presidency 50 years earlier. In 1863, Lincoln declared the final Thursday in November of that year to be a day of Thanksgiving.[319]

In June 1864 Lincoln approved the Yosemite Grant enacted by Congress, which provided unprecedented federal protection for the area now known as Yosemite National Park.[320]

Supreme Court appointments