Cleopatra's Needles

Cleopatra's Needles are a separated pair of ancient Egyptian obelisks now in London and New York City. The obelisks were originally made in Heliopolis (modern Cairo) during the New Kingdom period, inscribed by the 18th dynasty pharaoh Thutmose III and 19th dynasty pharaoh Ramesses II. In 13/12 BCE they were moved to the Caesareum of Alexandria by the prefect of Egypt Publius Rubrius Barbarus.[1] Since at least the 17th century the obelisks have usually been named in the West after the Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra VII. They stood in Alexandria for almost two millennia until they were re-erected in London and New York City in 1878 and 1881 respectively. Together with Pompey's Pillar, they were described in the 1840s in David Roberts' Egypt and Nubia as "[the] most striking monuments of ancient Alexandria".[2]

The removal of the obelisks from Egypt was presided over by Isma'il Pasha, who had greatly indebted the Khedivate of Egypt during its rapid modernization. The London needle was presented to the United Kingdom in 1819, but remained in Alexandria until 1877 when Sir William James Erasmus Wilson, a distinguished anatomist and dermatologist, sponsored its transportation to London.

In the same year, Elbert E. Farman, the then-United States Consul General at Cairo, secured the other needle for the United States. The needle was transported by Henry Honychurch Gorringe. Both Wilson and Gorringe published books commemorating the transportation of the Needles: Wilson wrote Cleopatra's Needle: With Brief Notes on Egypt and Egyptian Obelisks (1877)[3] and Gorringe wrote Egyptian Obelisks (1885).[4]

The London needle was placed on the Victoria Embankment, which had been built a few years earlier in 1870, whilst the New York needle was placed in Central Park just outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art's main building, also built just a few years earlier in 1872.

Damage to the obelisks by weather conditions in London and New York has been studied, notably by Professor Erhard M. Winkler of the University of Notre Dame.[5][6][7] Zahi Hawass, a former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities, has called for their restoration or repatriation.[8][9][10]

Alexandria

[edit]

The name Cleopatra's Needles derives from the French name, "Les aiguilles de Cléopâtre", when they stood in Alexandria.[12]

The earliest known post-classical reference to the obelisks was by the Cairo-based traveller Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi in c.1200 CE, who according to E. A. Wallis Budge described them as "Cleopatra's big needles".[13][14][a] At this point, both obelisks were still standing – it is thought that the toppling of one of the obelisks happened during the 1303 Crete earthquake, which also damaged the nearby Lighthouse of Alexandria.[14]

George Sandys wrote of his 1610 journey: "Of Antiquities there are few remainders: onely an Hieroglyphicall Obelisk of Theban marble, as hard welnigh as Porphir, but of a deeper red, and speckled alike, called Pharos Needle, standing where once stood the pallace of Alexander: and another lying by, and like it, halfe buried in rubbidge."[15] Two decades later, another English traveller Henry Blount wrote "Within on the North towards the Sea are two square obeliskes each of one intire stone, full of Egyptian Hieroglyphicks, the one standing, the other fallen, I thinke either of them thrice as bigge as that at Constantinople, or the other at Rome, & therefore left behind as too heavy for transportation: neere these obeliskes, are the ruines of Cleopatraes Palace high upon the shore, with the private Gate, whereat she received her Marke Antony after their overthrow at Actium".[16]

In 1735, the former French consul in Egypt, Benoît de Maillet, wrote in his Description de l'Egypte:[17]

Cleopatra's Needles: After this famous monument, the oldest and most curious in modern Alexandria are these two Needles, or Obelisks, which are attributed to Cleopatra, without anyone knowing too well on what basis. One is now overturned, and almost buried under the sands; the other still remains upright.

In 1755, Frederic Louis Norden wrote in his Voyage d'Egypte et de Nubie that:[18]

Some ancient authors have written that these two Obelisks were found in their time in the Palace of Cleopatra; but they do not tell us who had placed them there. It is believed that these monuments are much older than the City of Alexandria, and that they were brought from some place in Egypt, to decorate this Palace. This conjecture is well founded, as we know that at the time of the foundation of Alexandria, these monuments covered with hieroglyphs were no longer made, the understanding and use of which had already been lost long before.

Images from 18th and 19th century Alexandria show two needles, one standing and the other fallen. The London needle was the fallen needle.

The location is now the site of a statue of Egyptian statesman Saad Zaghloul.[19]

London needle

[edit]The London needle is in the City of Westminster, on the Victoria Embankment near the Golden Jubilee Bridges.

In 1819, Muhammad Ali Pasha gave Britain the fallen obelisk as a gift. However, Britain's prime minister at the time, Lord Liverpool, hesitated on having it brought to the country due to shipping expenses.[20]

Two prior suggestions had been made to transport the needle to London – in 1832 and in the 1850s after the Great Exhibition; however, neither proceeded.[21]

In 1867, James Edward Alexander was inspired on a visit to Paris' Place de la Concorde to arrange for an equivalent monument in London.[21] He stated that he was informed that the owner of the land in Alexandria where the British needle lay had proposed to break it up for building material. Alexander campaigned to arrange for the transportation.[21] In 1876 he went to Egypt and met Isma'il Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt, together with Edward Stanton then the British Consul-General. Alexander's friend, William James Erasmus Wilson, agreed to cover the costs of the transportation, which took place in October 1877.[21]

On September 7, 1940, the pedestal of the needle and one of its surrounding sphinxes were scarred by debris cast by a nearby bomb, dropped by a Luftwaffe plane as part of The Blitz. The damage is still visible today, and a plaque on the western sphinx records the event.

New York needle

[edit]In 1869, at the opening of the Suez Canal, Isma'il Pasha suggested to American journalist William Henry Hurlbert the possible transportation of an obelisk from Egypt to the United States.[22]

The New York City needle was erected in Central Park, just west of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, on 22 February 1881. It was secured in May 1877 by judge Elbert E. Farman, the then-United States Consul General at Cairo, as a gift from the Khedive for the United States remaining a friendly neutral as the European powers – France and Britain – maneuvered to secure political control of the Egyptian Government.[23][24]

Galleries

[edit]In Alexandria

[edit]-

1554 map of Alexandria showing both Cleopatra's Needles (standing and fallen) in Belon's Observations

-

1737 sketch from Frederic Louis Norden's Voyage d'Egypte et de Nubie

-

1798 (both needles visible)

-

1803 (only New York needle visible)

-

1809 (only New York needle visible)

-

1830s lithograph from David Robert's The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia

-

1870s, by Carlo Mancini

-

1880 (New York needle only)

-

1884 (New York needle)

-

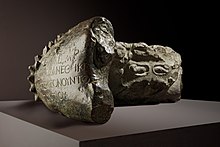

The inscribed crabs, as they were found

In London and New York

[edit]-

Cleopatra's needle being brought to England, George Knight, 1877

-

Close-up of London's Cleopatra's Needle

-

View of London's needle from mid-Thames, 2009

-

One of two sphinxes at the base of London's Cleopatra's Needle. The scars on the pedestal were from fragments of a bomb dropped during a World War II airstrike.

-

Close-up of one side of New York's Cleopatra's Needle

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The reference to Cleopatra claimed by Budge does not appear in available versions of Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi's work. See for example the 1800 bilingual version (both Latin and Arabic) al-Baghdādī, M.D.A.L. (1800). Abdollatiphi Historiæ Ægypti compendium,: Arabice et Latine. p. 111.; Arabic: ورايت بالاسكندرية مسلتين علي سيف البحر في وسط العمارة اكبر من هذه الصغار واصغر من العظيمتين, lit. 'In Alexandria, I saw two obelisks on the sea shore in the middle of the building, larger than these little ones and smaller than the two great ones'; Latin: Vidi in Alexandria duos Obelifcos fuper littore maris, in medio munimenti, majores his quidem parvis, magnis autem illis duobus minores, lit. 'At Alexandria I saw two obelisks near the shore of the sea, in the midst of the ramparts, the greater of the two small ones, and the smaller of the two large ones.' Also a 2021 translation al-Baghdādī, A.L.; Mackintosh-Smith, T. (2021). A Physician on the Nile: A Description of Egypt and Journal of the Famine Years. Library of Arabic Literature. NYU Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1-4798-0624-9.: Following a section discussing Ain Shams (Heliopolis): "I also saw two obelisks in Alexandria, on the seafront in the middle of the built-up area, bigger than these small ones but smaller than the two enormous ones."

References

[edit]- ^ Merriam, A. C. (1883). The Caesareum and the Worship of Augustus at Alexandria. Transactions of the American Philological Association (1869-1896), 14, p. 8

- ^ Egypt and Nubia

- ^ Wilson, Erasmus (1877). Cleopatra's Needle: With Brief Notes on Egypt and Egyptian Obelisks. Brain & Company.

- ^ Gorringe, Henry Honychurch (1885). Egyptian Obelisks. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (NCCO): Photography: The World through the Lens. John C. Nimmo.

- ^ Winkler, Erhard M. (1965). "Weathering Rates As Exemplified by Cleopatra's Needle in New York City". Journal of Geological Education. 13 (2). Informa UK Limited: 50–52. Bibcode:1965JGeoE..13...50W. doi:10.5408/0022-1368-xiii.2.50. ISSN 0022-1368.

- ^ Winkler, Erhard M. (1980). "Historical Implications in the Complexity of Destructive Salt Weathering: Cleopatra's Needle, New York". Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. 12 (2). JSTOR: 94–102. doi:10.2307/1493742. ISSN 0044-9466. JSTOR 1493742.

- ^ Winkler, Ε. M. (1996-12-01). "Die ägyptischen Obeliske von New York und London - Einfluss der Umweltbedingungen auf die Verwitterung / Egyptian Obelisks (Cleopatra's Needles) of New York City and London - Environmental History and Weathering". Restoration of Buildings and Monuments. 2 (6). Walter de Gruyter GmbH: 519–530. doi:10.1515/rbm-1996-5145. ISSN 1864-7022. S2CID 131283762.

- ^ Heyman, Taylor (2018-10-15). "Egyptian archaeologist 'ashamed' of London's treatment of Cleopatra's Needle". The National. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ "Hawass fears for Cleopatra's Needle". Ahram Online. 2022-11-10. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ "Hawass threatens to take 'Cleopatra's Needle' out of NYC". Daily News Egypt. 2011-01-09. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ Pfeiffer, Stefan (2015). Griechische und lateinische Inschriften zum Ptolemäerreich und zur römischen Provinz Aegyptus. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 9. Münster: Lit. pp. 217–219.

- ^ Lucas, Paul (1724). Voyage du sieur Paul Lucas, fait en MDCCXXIV, &c. par ordre de Louis XIV dans la Turquie, l'Asie, Sourie, Palestine, Haute & Basse Egypte, &c. Vol. 2. Rouen. pp. 24–25.

- ^ Elliott, C. (2022). Needles from the Nile: Obelisks and the Past as Property. Liverpool University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-1-80085-510-6. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ a b Budge, E.A.W. (1926). Cleopatra's Needles and Other Egyptian Obelisks: A Series of Descriptions of All the Important Inscribed Obelisks, with Hieroglyphic Texts, Translations, Etc. Books on the archæology of Egypt and Western Asia. Religious tract society. p. 166. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

Both obelisks were standing when 'Abd al-Latif visited Egypt towards the close of the XIIth century A.D., for, speaking of Alexandria, he says that he saw two obelisks in the middle of the building, which were larger than the small ones of Heliopolis, but smaller than the two large ones. He calls them "Cleopatra's big needles." One of them fell down, probably during the earthquake which took place in 1301, when the Nile cast its boats a bowshot on the land and the walls of Alexandria were thrown down.

- ^ Sandys, G. (1615). A Relation of a Journey Begun an Dom. 1610. Foure Bookes Coutaining a Description of the Turkish Empire, of Aegypt, of the Holy Land, of the Remote Parts of Italt, and Islands Adjoyning. Barren. p. 114. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ Blount, H. (1650). A Voyage Into the Levant (fourth ed.). Crooke. pp. 62–63. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ Le Mascrier, Jean-Baptiste; de Maillet, Benoît (1735). Description de l'Egypte ... compose sur les memoires du de Maillet ancien consul de france au Caire (in French). Genneau. p. 142. Retrieved 2022-11-11.

Aiguilles de Cleopatre. Après ce fameux monument ce qu'il y a de plus ancien & de plus curieux dans l'Aléxandrie moderne, ce sont ces deux Aiguilles, ou Obélisques, que l'on attribue à Cleopatre, sans qu'on sçache trop bien sur quel fondement. L'une est aujourd'hui renversée, & presque ensévelie sous les sables ; l'autre reste encore debout, & quoi qu'on ne voye point le piedestal sur lequel elle est posée, à cause des sables, qui l'environnent & le couvrent absolument, il est aisé de connoître en mesurant un des côtés de la base de celle, qui est renversée, que ce qu'on ne voit point de celle, qui est debout, n'est pas fort considérable. Les quatre côtés de ces Aiguilles sont couverts de figures hiéroglyphiques, dont malheureusement nous avons perdu la connoissance, & qui sans doute renfermoient des mystéres, qui resteront toujours ignorés.

- ^ Norden, F.L. (1755). Voyage d'Egypte et de Nubie: Tome premier (in French). De l'imprimerie de la Maison Royale des Orphelins.

Quelques Auteurs anciens ont écrit, que ces deux Obélisques se trouvoient de leur tems dans le Palais de Cléopatre; mais ils ne nous disent point, qui les y avoit fait mettre. Il est à croire, que ces Monumens font bien plus anciens, que la Ville d'Aléxandrie, & qu'on les fit apporter de quelque endroit de l'Egypte, pour l'ornement de ce Palais. Cette conjecture a d'autant plus de fondement, qu'on sçait, que, du tems de la fondation d'Aléxandrie, on ne faisoit plus de ces Monumens couverts d'Hiéroglyphes, dont on avoit déja perdu long-tems auparavant & l'intelligence & l'usage

- ^ DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Egypt: Egypt. DK Eyewitness Travel Guide. Dorling Kindersley Limited. 2013. ISBN 978-1-4093-4045-4.

- ^ "Egyptians are upset by Britain's disregard for a gift". The Economist. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- ^ a b c d Gorringe, Henry Honychurch (1885). Egyptian Obelisks. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (NCCO): Photography: The World through the Lens. John C. Nimmo. p. 199.

- ^ Gorringe, Henry Honychurch (1885). Egyptian Obelisks. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (NCCO): Photography: The World through the Lens. John C. Nimmo. p. 2.

- ^ "Obelisk". The Official Website of Central Park NYC. Central Park Conservancy. February 12, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ Farman, E.E. (1908). "Cleopatra's Needle - Negotiations by which it was secured". Egypt and Its Betrayal: Personal Recollections by Elbert Farman. ISBN 978-1-63391-136-9.

Further reading

[edit]- D'Alton, Martina (1993). The New York obelisk, or, How Cleopatra's Needle came to New York and what happened when it got here. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-680-0.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.